In Memoriam — Deep Ecology Champion and Watershed Media Collaborator, Douglas Tompkins

On December 8, 2015, the world lost one of the greatest conservation champions of this generation when Douglas Tompkins died unexpectedly in a kayak accident in southern Chile. He was 72 years old. Doug led an extraordinary life, first as an entrepreneur and founder and co-founder of businesses such as the North Face and Esprit, and for the past 25 years as a devoted conservationist, ecosystem restorer, adventurer and environmental activist. He was also my father-in-law.

Watershed Media co-founder, Roberto Carra, and I both met and worked with Doug at Esprit, a global fashion company that became a major innovator in design as well as workplace and social engagement. Esprit was the first global company I know of, for example, to ban cigarette smoking from its offices, stores and facilities. The in-house cafe was subsidized, there were sponsored daily fitness classes and yearly river trips. They took the lead on AIDS funding, employee volunteerism, and eco auditing. In the five years Roberto and I worked closely together there, Esprit pioneered the research and production of Ecollection, a clothing line solely dedicated to solutions such as organic cotton, low impact dyes and finishes, artisanal accessories and other developments still considered leading edge today.

Doug Tompkins sold his shares of the brand he helped create in 1991 and moved to a remote part of Chile, a country he had been exploring as a pilot, rock climber and kayaker for many decades. With this life change, he also shifted his powers as a communicator to the ideas of Deep Ecology. Originally conceived by Norwegian author Arne Naess, this philosophy holds that the environmental crises facing humanity require us to address fundamental root causes such as industrialization, overdevelopment, overconsumption, overpopulation, and biodiversity loss.

These were bold and controversial ideas for an environmental movement often more concerned with incremental progress than fundamental change. In an effort to catapult this discussion to the broader society, Doug launched a series of large format picture books, much in the spirit of David Brower's activist publications with Sierra Club Books decades earlier. He set up and funded the Foundation for Deep Ecology and began the production of hard hitting titles that combined essays with powerful photographs, often employing editorial devices more common in magazines and advertising than book publishing. Grassroots campaigns were linked to these books to draw media attention and build public awareness. The list of titles is impressive, including Clearcut: The Tragedy of Industrial Forestry, Fatal Harvest: The Tragedy of Industrial Agriculture, Plundering Appalachia, and at least two dozen more.

Watershed Media co-published CAFO: The Tragedy of Industrial Animal Factories as part of the Foundation for Deep Ecology series. Many years in the making, it debuted in 2010, featuring more than 450 photographs and over 30 wide ranging essays. Winner of the Nautilus Prize for Investigative Reporting, it remains the most damning publication about the wrongs of confinement animal agriculture to date. Watershed Media was also a co-publisher of Energy: Overdevelopment and the Delusion of Endless Growth, in 2012. When we produced Farming with the Wild in 2003, a book that highlighted farming models that combined agriculture and habitat connectivity, the Foundation for Deep Ecology became our primary supporter. At a time when the foundation community was keenly pursuing market-based solutions, Doug insisted that biodiversity protection had to be the core of any project he supported.

"Doug had a very strong sense of visual style," remembers Italian born art director and photographer, Roberto Carra. "From the aesthetic viewpoint, he was almost always right." As the owner of the first manifestation of the North Face, an outdoor mountaineering shop located in San Francisco, Doug visited the studio of Ansel Adams in Big Sur in hopes of securing evocative images of the California wilderness for his retail space. (His trip was successful!) Throughout his life Doug was constantly behind a camera himself, shooting pictures not only to document his life, but to direct ecological farming projects, land restoration, architecture and the many other endeavors he took on.

He loved photo editing but was an equally voracious reader and completely dedicated to making a lasting contribution to important contemporary discourse. Yet communication was but one facet of this extremely productive individual's life. Over the past 25 years, Doug and his wife Kristine Tompkins privately purchased over 2.2 million acres of land in Chile and Argentina and are in the process of creating 5 national parks and expanding others, essentially importing the long standing American tradition of conservation philanthropy to these countries. They also initiated "rewilding" efforts to reintroduce species such as the jaguar and anteater to their former ranges in northern Argentina.

"For Doug, no detail was small," remembers Roberto. These are important words for communicators to remember. And they are exceptional considering he held such a large view of the world and had the ability to build organizations and inspire the team work necessary to accomplish his visions.

Doug was amazingly focused. He was enormously talented and inspired. As a collaborator, he was extremely demanding and occasionally overbearing, but his standards were lofty, particularly those he kept for himself. He died among friends doing what he loved amidst the creaturely world he dedicated all his resources and energy to protect.

He will be sorely missed. The conservation efforts he inspired will live on.

Download a PDF of an article I wrote for the 2001 publication The World and the Wild: Expanding Wilderness Conservation Beyond its American Roots, by David Rothenburg and Marta Ulvaeus.

Learn more about Doug and Kristine Tompkins' work here.

"Unless we learn to share the Earth with all the other creatures on the planet, our own days are numbered. . . . We need to teach our children that each person must pay his or her “rent” for living on the planet, and that means demanding of our governments to make biodiversity conservation a priority. The primary means to this end will be more protected areas and, best of all, more national parks."

—Doug Tompkins

Photo by Beth Wald.

PBS Farm Bill documentary features Dan Imhoff and Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack

From the Founding Farmers to the modern Farm Bill, what has 200 years of progress brought to the table? More food at lower prices for sure, but also food fights over the environment, hunger, nutrition, and waste. In this closing episode of the 13-part PBS series Food Forward TV, Watershed Media co-founder Dan Imhoff, along with politicians, policy watchdogs and food experts take viewers on a personal tour through the history of food and agriculture in America. There’s an entry point for everyone in the conversation about how we feed ourselves.

Hermannsdorf: Symbiotic Farming

Snow is falling as the plane touches down at Munich airport. By the time we arrive in Hermannsdorf, an hour’s drive, the forests and rolling hills of the Upper Bavarian countryside are pillowed in a few inches of white powder. My wife, Quincey, and I are on a mid-winter European junket. We’ve tagged along with her father, Doug Tompkins, to visit the farm of Karl-Ludwig Schweisfurth, one of Germany’s (and the world’s) leaders in the sustainable food movement.

We start our tour at the Schweisfurth home, a delightful cottage decorated with all manner of livestock-inspired artwork. Karl-Ludwig is a tall, solid-boned, man with a mane of white hair and horn-rimmed spectacles. Now in his mid-80s, Karl-Ludwig grew the family business, Herta, into one of Europe’s largest meat processing corporations. He even based its expanding production lines on Oscar Mayer assembly operations, where his father sent him as a young man to study American innovation. “I am a butcher,” he says, deprecatingly, acknowledging the role and trade that life have given him.

After three decades in the meat packing business, however, Schweisfurth realized that the perpetual need for growth and ever-increasing disassembly line speeds came at too high a cost. He saw animal welfare, work conditions, health of the environment, food quality, and personal values plummeting as humans became further and further disconnected from the basic tasks of food production. In 1984, at age 54, he sold the business to start over again with his two sons. His career as a butcher wasn’t at an end. Rather, it became one skill among a larger set that requires farming, animal husbandry, meat processing, and retailing. The revamped family business soon included an inn, organic farm, restaurant, brewery, and bakery. It became a hub for local employment and the purchase of regionally produced organic grains and other ingredients.

Around his kitchen table, Karl Ludwig explains his concept of “symbiotic agriculture.” For more than two decades, he has been experimenting with raising different species of livestock on the same pastures using various mobile structures. The pigs protect the chickens from predators. The chickens eat parasites that might potentially sicken the pigs. The free ranging animals’ manure returns vital nutrients to the soil as they graze. Hundreds of acres of fields and livestock pastures at the farm, officially called “HermannsdorferLandwerkstätten,” are planted with various crops that provide forage for the animals or feed that can be stored for the winter. The farm’s workers are always striving for the best rotations of pasture crops to prevent pests from becoming too established, maintain healthy soil, and keep meat flavor as high as possible. On the kitchen table is a wooden model of a mobile group housing structure. I take off the wooden roof to inspect. The pigs’ quarters are downstairs. Poultry enter around the back and roost upstairs.

Finally it’s time to walk. We find plenty of animals out on the snowy landscape. Bavarian-styled chicken tractors house birds for both meat and eggs, active out in the cold winter day. Pigs are kept in permanent barns, as well as in smaller groups with simple wooden structures out in the fields. The barns have roomy outside stalls full of straw and covered internal stalls for feeding and weather protection. Families are raised together for their entire lives to honor the social hierarchies they develop at birth. Karl Ludwig delights in explaining the natural conditions in which the animals are raised. Below the barn, he points to a methane digester, a covered circular tank about the size of a yurt. There animal waste from the pig barns is processed. It generates electricity from captured methane gas. Compost for the farming operation is made from the remaining solid waste.

When we enter the slaughter plant, Karl Ludwig describes it as “the best plant I have ever designed.” It is white tiled, very clean. Chain mesh gloves and white aprons hang in orderly fashion. The animals are raised right on the farm and are moved to holding pens close by prior to slaughter. There is no long distance transportation involved that heightens stress in animals. The slaughter room and butchering operation are completely separated, he explains, so that no animal has a sense of imminent death. “I realize that in order to process animals I must kill them,” he says. “So I want to make both their lives and their deaths as compassionate as possible.” On a given week, 100 pigs, 20 bulls, and 100 sheep are killed, butchered and begin the curing and processing stage.

We tour a curing facility, a hall with a series of brick-lined rooms where meats are aged. The smell is sweet, sour and pungent. One room is filled with hanging hams that seem to be the German equivalent of Italian prosciutto or Spanish Serrano. Another room contains many racks of salamis. The air is peppery. The rooms have been cleverly designed using the thermal mass of the hill that the building abuts to provide optimum humidity and temperature controls with the least amount of energy.

In a processing kitchen we find large mixing machines for making sausages. Each stainless steel bowl could easily hold a person. Two ovens are presently occupied in the smoke curing of pork bellies. We see Karl-Ludwig’s guidance everywhere. The organizing principle, from start to finish is quality: for animals, workers, the environment, and eaters.

At last, we sit down to break bread. It is no wonder that the operation at Hermannsdorf is a popular tourist destination, with its beautiful restaurant and modern organic grocery. Karl-Ludwig’s family joins us at the table, a wide open floor plan with high ceilings and exposed wooden rafters, reclaimed from the former building, which was a mill. In addition to the restaurant they have a micro-brewery and a bakery. Both use ingredients from the farm and purchase grains, hops, and malt from regional farmers. We taste a goat cheese appetizer that is light, tangy and creamy. Spread on chewy dark German bread, it combines perfectly with a stein of the family Schwinebrau brown ale. This is followed by sautéd fennel and leeks, a crispy potato pancake, and a roast of veal that is shimmery and pink with a clean robust flavor. A lager beer, the paler brother of the ale, accompanies this main course. Karl-Ludwig carves the meat from his seat at the head of the table, generously passing samples to customers at the next table.

At the meal’s end, we present Karl Ludwig with a copy of the photo book, CAFO: The Tragedy of Industrial Animal Factories, that Doug Tompkins (Foundation for Deep Ecology) and I (Watershed Media) co-produced. He looks at the grisly photo on the front cover. It’s a dark scene inside an industrial hog facility. He points to me, shakes his head and with sad eyes asks, “You made this book?” I nod my head yes. “I finally decided to get out of the industrial meat business when I went inside one of these,” he says. He begins flipping through the large photographs of animal processing, waste lagoons, feedlots, and then puts it aside, knowing all too viscerally the heavy content featured in the book.

We have landed in one of the epicenters of the global healthy food movement. It’s a social current that is slowly sweeping the entire planet. I’ve been lucky enough to visit other places where science, art, land stewardship and food production combine at such profound levels. I see as this as our modern renaissance. Hermannsdorf is on the scale of the Prince of Wales’ efforts at the Duchy Home Farm in the English Cottswalds, Doug Tompkins’ pioneering farmscaping at Laguna Blanca in Argentina, and Wes Jackson’s visionary perennial polyculture at the Land Institute in Kansas.

Karl Ludwig is convinced that this approach to sustainably produced meat and grains—“symbiotic agriculture”—is not just a wealthy man’s hobby, not just a passing fad. It is the future that agriculture must somehow become. His son calls it “retro innovation,” the combination of land management and husbandry practices of the pre-petrochemical and pre-animal antibiotic past, with the understanding of ecological systems and small-scale agricultural technology of today. This is information rich, systems thinking: finding ways for the farming to fit the land, and for the land to feed the animals.

A day’s visit is not enough. We need more time to explore. I have dozens more questions. But we must be on the road to our next destination, and leave, having tasted, experienced, and fully sensed Hermannsdorf, a lighthouse to the world of food and farming.

Links:

Doug Tompkins’ pioneering farmscaping at Laguna Blanca inArgentina

Indoctrinating the Youth: National Pork Board Spins Yarns About Modern Meat Production

By Dan Imhoff

A few months ago, while reading an article about an independent pig farmer, I stumbled upon a curious case of “social engineering.” The farmer was lamenting how hard it was to place a story about his responsibly raised pork. He cited the National Pork Board—with its $60 million annual budget and arsenal of media resources to promote “the Other White Meat”—as a chief obstacle for small farmers.

A website link in the the article led me to a coloring book called “Producers, Pigs & Pork.” Innocuous at first glance, it is a book (or downloadable PDF) of simple drawings inviting kids to color in between the lines and “learn more about pigs.” Published as part of the “Pork4Kids” program, the storytelling takes place on a fourth grade level. And given the realities of contemporary livestock production, it’s quite a tale.

We travel with narrator Billy to a 100 year-old farm where we meet smiley farmer Jones and fresh faced veterinarian Dr. Sarah. Huge feeding silos and windowless barns are outlined for kids to color in. “This is fun!” Billy exclaims. “I’ve never been to a pig farm before.”

Young minds are told that fast growing pigs need lots of corn and soybeans (not table scraps) to grow to a market weight of 270 pounds, that veterinarians are there to look after them if they fall ill, and that pigs no longer grow up in the mud so they can stay healthy and happy.

The veterinarian’s prominence in the story is especially curious. Maps and surveys done by the American Veterinary Medicine Association paint a completely different picture of veterinarians on large livestock operations. In fact they detail a lack of veterinarians in many states where livestock production has consolidated: Iowa, Illinois, Minnesota and North Carolina. What’s more a battle is raging right now over the abuse of antibiotics, fed routinely in feed and water rations to animals, without veterinary consult.

Of course, in the real world of Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations, the stench from 2,500 pigs jammed into a single hog barn would send Billy running for the exit clutching his barf bag. Billy might have nightmares after witnessing the crazed repetitive behaviors like bar chewing and pacing that intensive confinement induces in animals who naturally want to spend the day wallowing in mud, searching for food, and socializing in appropriate numbers.

According to the National Pork Board, “pigs can’t use all the feed they eat, so they produce manure. … this makes our crops grow better.” There is no mention that the immense output of untreated animal waste contained in a holding pond on the Jones’ modern factory farm could be equivalent to a small city. Or that the manure contain hundreds of compounds including antibiotics, hormones, heavy metals, and toxic gases.

As the story line of “Producer, Pigs & Pork” unfolds, so does its inherent magical realism. All is well down on the “farm”, even though the animals’ lives are any where close to natural. Visitors wear boots and coveralls to avoid passing germs to animals. In one final move of creative story telling, pigs turn into roast, pork chops, ribs and other cuts without transport to or slaughter at a processing facility.

This and a number of other coloring books are funded by the Pork Checkoff Program, a product of the 1985 Farm Bill and administered by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. U.S. pork producers and importers pay $0.40 per $100 of value when pigs are sold and when pigs or pork products are brought into the United States. The $70 million dollar annual budget for communications, research, and marketing is significant.

The Factory Farms of Lenawee County

Eastern, Michigan, March 2013 — Rolling across North Carolina, Indiana, Illinois, Washington, California, and today, eastern Michigan, I’ve seen first-hand the impacts of industrial dairy, poultry, and hog factories on rural communities. I admire the people who fight back against the invasion of factory farms. I seek them out, trying to see the land from their eyes. But no matter how many times I experience it, I still find unpalatable a business model that’s based on marginalizing animal welfare and polluting your neighbors’ air, land, water and quality of life in the name of profit and cheap food.

Eastern, Michigan, March 2013 — Rolling across North Carolina, Indiana, Illinois, Washington, California, and today, eastern Michigan, I’ve seen first-hand the impacts of industrial dairy, poultry, and hog factories on rural communities. I admire the people who fight back against the invasion of factory farms. I seek them out, trying to see the land from their eyes. But no matter how many times I experience it, I still find unpalatable a business model that’s based on marginalizing animal welfare and polluting your neighbors’ air, land, water and quality of life in the name of profit and cheap food.

Lynn and Dean Henning are guiding me on a tour of the CAFOs of Lenawee County. It’s a cold morning in early spring. The landscape is leached of color. The ponds are thick with ice. An occasional snowflake flutters from wooly clouds.

“When they spray manure in the winter, sometimes you can see it hanging frozen from the irrigation booms,” says Lynn from the back seat. “We call them ‘poopsicles.’”

“What’s it like here when spring arrives?” I ask, imagining a painterly transformation of the countryside with grass, foliage, blossoms, songbirds.

“Springtime smells really bad,” she answers.

Dean is driving. He is silver haired, in his late fifties. He has cut back on farm work since suffering a heart attack and a subsequent quadruple by-pass surgery a few years ago. We travel by “Henning Hwy.,” named after his grandfather, the first homeowner to bring electricity to the neighborhood. Dean still farms a few hundred acres of corn and soybeans, manages a few hundred acres of forestland, and maintains a massive garden that produces a prodigious quantities of tomatoes, sweet corn, and other heirloom vegetables for family and friends.

I already know Lynn Henning as the anti-CAFO warrior with waves of white hair who won the prestigious 2010 Goldman Environmental Prize. Lynn and I have met a few times as fellow conference speakers. She and Dean have been kind enough to let me tag along on one of their thrice-weekly surveys of creeks and drainages, scouting for discharges from the dozen or so dairy CAFOs spaced at five-mile intervals around their area.

With its vegetable, tree fruit, grain and livestock production, Michigan boasts the country’s most diverse agricultural output next to California. But Lenawee County is corn and soybean country. Its fields follow the rolling contours of the land. Broad fields are interwoven between small belts of trees and complex drainages that carve through the sloping lands, sometimes flattening out in low-lying wetlands. This is precisely the challenge of concentrating livestock in this area: how to keep the waste from running off fields into the many surface and underground drainage systems that feed creeks, streams, river arteries and eventually flow into the now mightily polluted Lake Erie.

Our first stop is Hartland Farms, a Concentrated Animal Feeding Operation (CAFO) with 1,000 dairy cows and 2,000 acres of cropland. As Lynn rattles off the complicated web of partnerships that make up its ownership, it becomes immediately obvious to me why a CAFO is so aptly referred to as a “factory farm.” The buildings are sheathed in steel. Cows are nowhere to be seen. They are housed inside by the hundreds in linear stalls, moving only to lie down or take their turns at the electronic milking parlor. Waste exits one end of the facility the way a vertical smokestack might release pollution skyward. Instead of smoke, the CAFO pipe spews concentrated liquid animal waste—rich in nitrogen, phosphorous, ammonia and other chemicals and laden with bacteria such as fecal coliform and E. coli. The waste is temporarily stored in nearby holding lagoons that are bermed into ponds as long as football fields and deep enough to contain millions of gallons of waste. Waste off-gasses into the atmosphere that floats across the surrounding community. Waste is spread on nearby fields or pumped directly into underground irrigation pipes beneath fields.

“They plaster it on 8 inches thick and spray right up to the roadsides,” says Lynn.

“In liquid form,” adds Dean, “it doesn’t stay on the ground too long.”

The image of 100-acre fields smeared with CAFO manure more than a half a foot deep is nauseating. In fact, I can see the brown green shadow from a recent ground application glistening between rows of stubble left from last year’s corn harvest.

Dean and Lynn make the rounds of potential discharge sites. A drain can be a simple grass-lined gulley that moves through the low point of a field. It could be a culvert that spans beneath a road. Eventually the water moves onto successively larger waterways, like the South Branch of the River Raisin.

In order to monitor what is happening to their community, the Hennings, along with other members of the Environmentally Concerned Citizens of South Central Michigan, have become citizen scientists. Armed with a variety of hand-held devices, volunteers can monitor for nutrients, chemicals, bacteria, antibiotics and biological oxygen demand. Samples are sent to a lab if results indicate potentially dangerous contaminants. Any alarming findings are officially reported to the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality.

Rural agricultural conflicts like these are not just the result of too many humans coming up against too few resources. These fights have been going on for a very long time. Way back in 1610, English landholder William Aldred claimed that his neighbor, Thomas Benton’s pig sty, was sited too close to his home. Aldred argued that the livestock operation was violating his rights as a community member. Upon hearing the case, King Charles I’s court ruled in Aldred’s favor, deciding that no one has “the right to right to maintain a structure upon his own land, which, by reason of disgusting smells, loud or unusual noises, thick smoke, noxious vapors, the jarring of machinery, or the unwarrantable collection of flies, renders the occupancy of adjoining property dangerous, intolerable, or even uncomfortable to its tenants." In other words, it’s against common law to stink up or foul the neighborhood.

Four centuries later, it is still to the courts where citizens must turn when their air, water, and health are violated by intensive concentrations of animals.

We make a stop at what looks like a recently constructed CAFO facility. There are four white hangar-like barns. Sandwiched between the four barns is a fancier brick building that must serve as the main office. But something is amiss. There are no trucks in the lot. There’s no one around at all. The mailbox is tilted at a funny angle. The place is abandoned. Apparently, the CAFO went belly up. It’s been taken over by the bank and is for sale.

Factory farms, I learn, are a relatively new phenomenon in Lenawee County. The first mega-dairy arrived in 1999 as the Hudson area became a target of the Vreba-Hoff Dairy Development syndicate. This family, with Dutch origins, is now legendary across the Midwest for fabricating an elaborate Ponzi scheme that started over 90 mega-dairies, mainly with investments from European families they conned into coming to America. Facilities were often never completed or were simply unprofitable. Environmental violations were routine. Even as dairies failed, Vreba-Hoff continued to attract more investors, expanding further into rural communities. Many investors were forced into bankruptcy. Creditors lost millions. The CAFO conmen took the money and skipped town.

“Small town drama,” says Lynn.

Indeed. The more you look behind the curtain, this CAFO model becomes a serious shell game. Pack as many animals on a particular property as an agency will authorize with a pollution permit (if the agencies even require one.) Convince local governments to build new roads and other infrastructure. Rake in hundreds of thousands in US Department of Agriculture subsidies to help pay for waste management costs, and on top of that, take advantage of feed subsidies, taxpayer supported crop insurance and disaster payments for your croplands. Degrade the health of the neighborhood with waste emissions and stench, slowly driving homeowners out, then buy up their devalued properties in the process.

“They use manure as a weapon,” says Dean.

We are passing through the half-boarded up farming town of Medina. It’s a victim of what can only be described as economic undevelopment.

“Why don’t people fight back?” I ask.

“People are afraid to pick fights,” says Lynn. “It’s like the town in A Civil Action. People have lived here forever. Many are convinced that they need this system, that they’ll earn money renting their land to the CAFOs for field applications.”

“Even when that waste damages their soil and lowers their yields,” adds Dean.

“People will drop a note in the mailbox or take me aside every once in a while and thank me for speaking out,” says Lynn.

I think about the twisted and somewhat tragic logic at work: an unhealthy food production system that people somehow accept as inevitable. A system where many of the real costs of production—effects on human health, impacts on shared water resources, basic costs of feed and waste management—are passed off on local communities and federal taxpayers. I ask Lynn and Dean to talk about the words and terminology which industry uses to describe these events I am seeing.

“They always speak of ‘odor,” says Dean, “never of toxic pollution.”

“Waste runoff and lagoon overflows after heavy rains is always ‘storm water,” says Lynn.

“Waste running into the creeks is a ‘discharge,” says Dean.

“Lagoon waste spread across the farm fields is ‘sediment,” says Lynn. “But it’s never dry and it’s not sediment. And underground pipes that drain straight into the creeks are ‘sub-irrigation systems.’”

We stop at an infamous site where a 20-acre wetland was filled with CAFO waste a few years back.

“The EPA was here to see it,” says Lynn.

I begin to fear that in my zeal to document this tour with photos I’ve been breathing nasty air. It’s no doubt on my boots and clothes and perhaps in my respiratory system.

“What if you could buy up one of these defunct CAFOs and turn it into a demonstration farm for a new kind of pasture-based, healthy agriculture?” I ask.

“I wish we could,” says Lynn.

Dean describes a farm. “A 640-acre section is a square mile,” he says. “You would want to keep at least 160 acres in woodland. The rest could be fenced off so that fields could be rotated between pasture and row crops. At two acres per cow, you could have a diversified farming operation,” he says. “This model could be very effective on smaller operations.”

I can almost imagine a new era of integrated agriculture catching on in Lenawee County. As someone once said, it’s hope that makes us human.

The Land of Stinkin’: When a Mega Dairy Takes Over

Imagine a series of pits that, if combined, would cover an area 40 acres in size carved 20 feet deep. Laid out as a perfect square, each side is 1,320 feet long, enough to hold 16 football fields. Now imagine it full of millions of gallons of festering manure from over 5,000 dairy cows plunked down into rural Jo Daviess County in northern Illinois. Imagine also, that these cesspools would be excavated from a porous Karst geological formation, with the propensity to percolate directly into the groundwater, along with a cocktail of nitrates,phosphorous, hydrogen sulfide, bacteria, and other substances like antibiotic drugs.

If your state’s Environmental Protection Agency doesn’t bother fulfilling its obligations to permit such potential pollution hazards under the Clean Water Act, you have little choice but to start your own citizen activist organization. For three years, the HOMES group (Helping Others Maintain Environmental Standards) has been emptying their pockets for attorneys fees, organizing rallies, documenting abuses, and constructing a legal case against a California mega-dairy that wants to—as they see it—invade their community, an agricultural region with many legacy farms spanning multiple generations.

The challenge before the HOMES group is made all the more difficult because Illinois communities have lost the ability to refuse such a siting of an industrial animal factory operation in their area for concerns of protecting their own public health. “Local control” over such decisions, in Illinois as in many other states, has been relegated to the state level. In fact, just this week a HOMES' group appeal was denied by the Illinois Supreme Court, affirming that the state's Department of Agriculture has the ultimate say in CAFO siting decisions, and stripping citizens' rights to sue for improper implementation or enforcement of regulations.

I participated in a community discussion about CAFOs sponsored by the HOMES group last week. It was an opportunity to listen to talks from long-time activists Dr. Kendall Thu of Northern Illinois University (contributor of a great essay to my CAFO book) and Dr. John Ikerd, retired agricultural economist at the University of Missouri, whose work greatly informed the book’s pieces on the community impacts of industrial animal factory agriculture. I also had a good chance to meet other committed anti-CAFO activists, such as grain farmer Karen Hudson and public interest attorney Danielle Diamond, both with theSocially Responsible Agriculture Project.

This leg of the CAFO outreach campaign started about an hour west of Chicago, driving west and south through the Land of Lincoln, known by the anti-CAFO activists as the Land of Stinkin’. There are over 3,200 CAFOs in the state, primarily hog and dairy operations. To pump a steady stream of feed into these protein factories, Illinois produces a staggering amount of corn. We drove for hours and hours at the 65 mph speed limit, passing field after monoculture field of corn, fields right up to the highway, right up to farm houses, right next to mutated suburban developments with barely a forest or hedgerow or clump of trees in sight. As they say, planted “fencerow to fencerow.” In this day of soaring commodity prices, soaring demand for animal feed and ethanol, it seems the only way an Illinois farmer would maintain any habitat at all is if the government (aka taxpayers) pay them for it.

The mega-dairy that the HOMES citizen activist group is fighting against is owned by A. J. Bos, a corporate agribusiness from California. It has already established one of the country’s largest dairies in northeastern Oregon, Threemile Canyon, which I have visited and am told is now the third largest emitter of airborne ammonia in the nation—no small achievement if true. One of the departing acts of public service of the Bush administration was to remove Environmental Protection Agency restrictions on reporting of air emissions including ammonia, an airborne pollutant and health hazard that can literally travel for miles from a livestock operation. The CAFO industry has been given a get out of jail free card when it comes to Clean Air Act violations.

This large-scale industrial assault is set against the backdrop of the unraveling meltdown of the Fukishima Daiichi nuclear power plant in Japan and I can’t help thinking of the out of control scale of our industrial operations. The CAFO industry is essentially telling us they’re too big to fail, we need their massive confinement systems if we want a cheap and abundant food supply. The costs of polluting a community’s groundwater, eroding their living standards, degrading their air quality and filling the countryside with the odors of thousands of cows producing more manure than milk on a daily basis and never touching a blade of grass are simply the price of cheap dairy products. What they don’t say is that the jobs a CAFO actually brings in to an area will most likely be very few and low paying. It will also spell the end for numerous small and mid-size independent producers in the region. And in time, once a community is opened up to the animal factory industry, it begins a downward economic spiral with few other development options.

As the HOMES group fights with every breath to prevent becoming an ecological sacrifice zone, it appears that the owners of California-based A. J. Bos have no intentions of living anywhere near the operation. State and federal regulators have made the expansion of such filthy businesses possible. It is humbling to witness such a tragic abandonment of civic defense.

Glimmers of hope remain. Although construction of the mega-dairy is well underway, the barns remain incomplete and no animals are confined yet. Last October, a bright purple leachate of rotting silage, applied onto fields of the A. J. Bos land, contaminated a tributary to the Apple River. As a result, the US EPA is now questioning whether this CAFO can possibly be a “zero discharge facility” as the corporation has alleged. (That's essentially the way the system works. A CAFO promises they are not going to discharge, and the government believes them.) Meanwhile, a second citizens’ activist group, Illinois Citizens for Clean Air and Water, is successfully petitioning the US EPA to withdraw the Illinois EPA’s Clean Water Act permitting authority because of their failure to properly regulate existing CAFOs. The pressure is now on the Illinois EPA to step up their regulatory oversight or risk US EPA taking over administration of the Clean Water Act in the state.

In northern Illinois, and across the country, everyday citizens are doing the work of the state and federal government to prevent a complete fouling of their communities by industrial animal factories. This is hardly the time to dismantle the Environmental Protection Agency, a pursuit senators and representatives from both sides of the aisle are currently attempting. In many states, the Clean Water Act remains one of the only tools that offers citizens any kind of legal recourse and environmental protection from installations such as shit spewing absentee landowner corporate mega-dairies. In an age of increasing voluntary corporate compliance, community self-preservation hangs by barely a thread.

Bag the "Ag Gag" Bills

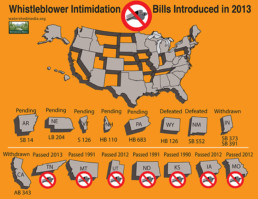

When might it be punishable to report a criminal activity? When it takes place inside a poultry warehouse, slaughterhouse, or on a cattle feedlot. That’s the upshot of a new wave of so-called “ag-gag” bills passed in state legislatures around the nation, the latest of which, AB 343, was introduced in California last month.

When might it be punishable to report a criminal activity? When it takes place inside a poultry warehouse, slaughterhouse, or on a cattle feedlot. That’s the upshot of a new wave of so-called “ag-gag” bills passed in state legislatures around the nation, the latest of which, AB 343, was introduced in California last month.

“Ag gag” laws have been put forth by the meat industry to criminalize the reporting of animal cruelty by anyone—journalists, activists, or whistleblowers. They are intended to prohibit the release of videotapes or photographs that document what happens inside factory farms and meat processing facilities, often with the threat of jail time. The real goal of these laws is to “chill” a person’s resolve to make public any illegal behavior such as beating or torturing captive animals, often using the police to seize their materials.

Whistle blower intimidation laws incite the ultimate cynicism about politics. For instance, the California bill is titled, “Duty to Report Animal Cruelty,” when in fact, its true aim is to squelch dissemination about the brutality of factory farming. If passed, AB 343 would require would-be whistle blowers to submit any visual evidence to law enforcement within 48 hours of taking a photograph or video or be subject up to a $500 fine. It also encourages the submission of any proof to the owner of the animals.

This would effectively force reporters to forfeit their anonymity. A worker might face retaliation from an employer. A journalist might not have time to adequately pursue a lead. Offending operators would be alerted that they are under suspicion. Meanwhile, industry maintains the appearance that it cares about animal welfare.

Big agricultural lobbies are desperate to avoid the kind of public relations disaster that befell the Hallmark Meat Packing Company. In 2008, secret cameras showed downer dairy cows being chained, dragged, and electrically prodded to slaughter at Hallmark’s facility in Chino, California. Such illegal practices were exposed by a disillusioned plant worker and the Humane Society of the United States. The USDA’s Commodity Procurement Branch, which distributes beef to the National School Lunch Program, was one of Hallmark’s biggest customers. The ensuing news coverage resulted in the largest recall of meat products in history and the ultimate closure of the plant.

Kansas, Montana, and North Dakota already have laws making it punishable to photograph an agricultural operation without consent of the owner. Utah, Missouri, and Iowa passed ag gag laws last year. In Iowa, where recent undercover videos have shown blatant animal abuse at egg and hog facilities, a first offense can land you in jail for up to a year. A second offense is considered an aggravated misdemeanor with up to two years jail time.

What’s happening in California is part of a nationwide effort. Already this year, whistleblower suppression laws similar to California’s have been filed in Arkansas, Indiana, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New Mexico, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Vermont, and Wyoming.

The timing of this legislative push is extremely troubling. The federal government’s budget sequestration could significantly reduce funding for USDA meat inspectors. The system is already challenged to keep up with continual changes in production lines that process animals at ever-increasing speeds. That means even as the government has less resources for oversight, industry is working to suppress whistle blowing.

Why is the meat industry on the defensive? Even perfectly legal practices are often distasteful to the public. In the face of rising public awareness about genetically modified crops, contaminated eggs, downer animals, etc., the meat industry has been jolted into anti-democratic tactics to muzzle its critics.

Newly elected California Assemblyman, Jim Patterson (23rd District), introduced AB 343 to the state legislature with the backing of the California Cattlemen’s Beef Association. While it might appease the powerful California meat lobby, this law would go against the will of California’s majority. Most citizens want animals to be raised more humanely. California’s Proposition 2, the Prevention of Farm Animal Cruelty Act, passed with 63 percent of the vote. Restrictions on animal cages are slated to go into effect January 1, 2015.

When government fails to fulfill its regulatory oversight, citizens—including the news media—often have no choice but to become their own watchdogs. There is a noble American tradition of journalism related to food production concerns. At the turn of the 20th century, Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle described appalling conditions in Chicago’s slaughterhouse district. Its publication greatly influenced new laws to regulate food safety and meat processing. Now is the time to turn the tide against a national assault on greater transparency and meaningful reform in the food system.

The Farm Bill is Really A Food Bill

America’s first Food Stamps were orange or blue. Citizens eligible for government relief bought a one dollar orange ticket at face value, redeemable for any food item. Accompanying every orange stamp was a free blue ticket worth 50 cents, that could be used to buy surplus food items: meat, milk, eggs, or seasonal produce that the government purchased from farmers. This was the 1930s, and federal nutrition assistance, along with support to help farmers conserve the soil and earn fair prices, were essential elements of what we know today as the Farm Bill. Food stamps were what helped many desperate families put food on the table.

Eighty years on, Food Stamps continue to be one of the ways America grapples with its hunger problems. Paper coupons have given way to less stigmatized Electronic Benefits Transfer (EBT) cards—monthly monetary allotments assigned to a debit card. But the numbers are staggering. As a result of the economic contraction that started in late 2007, nearly 50 million people, one-third of them children, are now in poverty (up from 31 million in 2000). The number of U.S. citizens applying for food stamps, now known as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), has nearly tripled since 2001. In the month of October 2012 alone, three years into our economic “recovery,” nearly 1 in 7 Americans—47.5 million people— participated in the SNAP program.

These monthly Food Stamp enrollment tallies, however, don’t demonstrate the magnitude of poverty in the U.S. or the true function of the program. Critics of big government and social assistance often use the Food Stamp program as a punching bag for wasteful, excessive and fraudulent entitlements. But the fact is, a majority of people use Food Stamps as a temporary safety net between jobs—not as a permanent solution to hunger. Many are working families struggling to raise themselves out of poverty. USDA estimates that as many as 65 million Americans received SNAP benefits for at least one month during 2012—1 in 5 Americans.

“People don’t aspire to enroll in the SNAP Program,” says Stacey Dean, of the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities. “By far, the SNAP Program serves people who, because of the stress and hardship of poverty, face a genuine lack of access to healthy and affordable foods.”

Even in the era of 99-cent value meals, Food Stamps play a crucial role in providing calories to hungry Americans. As the economic recovery drags on, and as deficit reduction talks heat up, the annual Food Stamp budget—which now totals $75 billion per year—will become a prime target for cost cutters. The values of food assistance must be part of those deliberations.

- Food stamps are part of the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Farm Bill. While most people associate the Farm Bill with subsidies for corn and soybean farmers, in fact, its largest line item is the SNAP program, which accounted for more than 75 cents of every dollar spent by the Department of Agriculture in 2012.

- The Food Stamp program mainly serves people in need. The USDA’s official term for hunger is “food insecurity.” These are people who regularly skip meals because of a lack of resources. It could be a senior citizen, with hefty medical bills and fixed income, who must choose between medicine and food. Or it could be one out of every six American children for whom Food Stamps along with the School Lunch, Breakfast and Snack programs governed by the Child Nutrition Act, are an essential bridge between hunger and starvation.

- Many food stamp recipients have employment income. Over 60 percent of participating households earn income that they contribute toward the family food budget—it’s just not enough to stave off hunger.

4 . No one is buying filet mignon with food stamps. The maximum monthly allotment—$200 per individual and $668 for a family of four—nets out to around $2 per meal. Big city mayors, celebrity chefs such as Mario Batali, and others have taken on the challenge of living on a Thrifty Food plan for a week at a time. All have complained about temporarily foregoing caffeine, snacks, and things many Americans take for granted—and feared running out of money.

- Food stamps function as an economic stimulus. President Obama’s economic stimulus plan (the American Recovery Reinvestment Act of 2009) provided tens of billions of additional dollars for food assistance programs. Studies show that every Food Stamp dollar spent actually generates at least $1.74 in the broader economy. This is called a “multiplier effect.”

USDA Secretary Tom Vilsack regularly reminds audiences that the Food Stamp program helps farmers too. “Producers get somewhere between 15 and 16 cents of every food dollar that’s spent in a grocery store and a restaurant,” he told the American Farm Bureau Federation in Nashville in January 2013. “And to the extent that families are empowered during struggling times to be able to buy adequate groceries for their family, at the end of the day that also helps American producers.”

- Food stamps have a positive effect on health and nutrition. According to the Food Research and Action Center, the SNAP Program lifted nearly 4 million Americans above the poverty level in 2011 by boosting monthly income. Providing relief from hunger yields positive impacts on body weight, learning abilities, and reducing the incidence of chronic diseases—particularly among children.

The recent rise in Food Stamp enrollment offers an important window into the crisis of poverty and hunger in America. Some might view it as solid proof of failed economic policy. Instead we should look at as a way to assess whether and how government is doing its duty—investing in the health and well-being of all of society for the long term.

Clueless About Food and Agriculture?

Outside of First Lady Michelle Obama’s “Let’s Move” campaign to urge kids to exercise more and eat better, this administration remains largely indifferent to the disaster that is the country’s outdated food and agriculture policy. USDA Secretary Tom Vilsack recently argued that rural America has become politically irrelevant—a possible explanation for why the House refused to even consider a vote on a new Farm Bill last year. Maybe it’s something else. It could be that the present Congress and Administration are simply clueless about the severity of our food and farming crises.

Riding the coattails of the fiscal cliff bargain, the 2008 Farm Bill—three months past its “renew by” date—got a nine-month extension shortly after New Year’s Day. The extension could have included funds to preserve programs that help rural America and rebuild a food and farming system around the challenges of the 21stcentury. Instead, the policy—concocted in backdoor fashion without any public input—might as well have been written by lobbyists from the crop insurance, finance and agrochemical industries.

The Farm Bill extension bears little resemblance to the plan hotly debate and passed by the Senate last summer. While by no means ideal, that Senate plan would have clipped excessive commodity subsidies and reduced but still preserved important programs for conservation, organic agriculture, and rural development. This Farm Bill extension will continue sending $5 billion in direct payments to landowners whether they farm or not, whether they experience losses or not. (Both Republicans and Democrats favor eliminating such subsidies.) By extending rather than writing a new five-year Farm Bill, Congress did, however, manage to avert the dreaded “dairy cliff.” This would have reverted to a 1949 dairy subsidy program causing milk prices to spike to about $7 a gallon.

Kicking the Farm Bill down the road means we continue to invest in a backward agriculture policy. Because nothing was done to reform cotton subsidies, the US will continue to send $150 million in 2013 to Brazilian cotton farmers. This is the result of a lingering World Trade Organization ruling that declared previous US cotton supports trade distorting. Meanwhile, as Brazilian farmers benefit from the Farm Bill extension, the big losers are dozens of programs that train the next generation of US farmers and ranchers, invest in on-farm renewable energy, assist organic growers, expand farmers markets, and rebuild the infrastructure of a regionally-diversified food system.

Contrary to what many might think, the US faces a mounting list of rather alarming food and farming related challenges. Over 15 percent of the American population—mostly retired, disabled, children or underemployed—depend on food stamps, the largest budget item in the Farm Bill. Last year’s severe drought affected two-thirds of all agricultural counties, impacting crop yields, raising grain prices, and forcing livestock owners to sell off herds. Unpredictable weather patterns, we are told, are now the norm. “Superweeds” occupy 60 to 80 million acres of the country’s farmland as a result of a large-scale shift to genetically engineered, herbicide-resistant crops. Our research budgets into innovative farming strategies to address such problems are shrinking rather than expanding.

The Farm Bill exists to address problems, like these, that are not easily solved by the free market. A smarter Farm Bill would offer assistance to farmers to take care of natural resources, help for those who can’t get enough to eat, and funding for forward-thinking research to help farmers stay ahead of environmental challenges.

The good news is that the door is not yet closed on a Farm Bill. The most recent short-term extension means that a new five-year Farm Bill could be written and voted on by September. Despite “Farm Bill fatigue” setting in among many citizens who care about agriculture policy, the time to set the terms of this debate is now, as Congress struggles with the challenge of fiscal austerity and the national debt. We still have the opportunity to make the changes necessary for a healthier, more secure, and conservation-based food system. Representatives need to repeatedly hear our concerns.

Here are a few ideas that voters should be pestering the 113th Congress about:

Full funding for conservation programs to protect topsoil, clean air, fresh water and safeguard natural habitat;

Reform of the crop subsidy rules to exclude millionaires from government handouts and limit how much an individual entity can receive;

Changes to crop insurance including limits on federal funding to insurance companies and strict environmental stipulations for farming operations that enroll;

Expanded support for sustainable and organic agriculture through cost-share programs, research, and market development;

Continuation of programs that invest in a new generation of farmers and ranchers;

Initiatives aimed at increasing the accessibility and affordability of healthy nutritious foods, particularly among the young and aging.

Holding our collective breath for change won’t help. The healthy food movement needs to speak more loudly and preferably in unison on these issues. Otherwise we’ll get more of the same: food and agriculture policy that is clueless about the real problems we face in the years ahead.

Follow the Farm Bill discussions at

Sustainable Agriculture Coalition

PINK SLIME by Becky Weed

I am a farmer/I am a citizen, and this is what ‘we’ are being told:

We must raise or at least finish our animals in cages and feedlots because it is ‘more efficient’.

Even our animals that start on pasture must end in feedlots, because they ‘finish more quickly’.

We must feed heavy grain diets to ruminants evolved to live on grass, inducing low-grade illness and the practice of feeding subtherapeutic antibiotics --- because that ‘enhances growth rates’.

We cannot quit subtherapeutic feeding of antibiotics because it would be too expensive.

We must implant growth hormones to make our animals grow faster because that is most ‘profitable’.

We can extend the output of such feedlots by scavenging the meaty bits admixed with pathogen-prone fatty exteriors, and disinfecting the resultant ‘pink slime’ with ammonia gas. We must serve this augmented ‘hamburger’ to our populace, unlabeled, because it ‘adds value’.

We must spray chemicals on our fruits, vegetable, grains, and into our soils, because it is ‘cleaner’.

We must work, or hire others to work, in conditions that affluent Americans shun for themselves or their children.

We must burn up the carbon in our once-organic-rich soils in order to maximize production with ‘modern’ farming. We must displace food production with ethanol production because it ‘conserves’ carbon-based fuels.

We must purchase crop insurance via government programs rather than building our own crop insurance by building our soils and our crop diversity.

We must grow crops with diminished nutrients because modern, high-yielding Wonder Bread varieties are ‘best’.

We must feed the food derived from such management to our children.

We must plant only a few crops for fuel and livestock feed on such a vast portion of our continent that we disrupt the natural migrations of birds, mammals, pollinators, and water, because it is more ‘efficient’.

We must kill even our most iconic and remnant species, such as buffalo, because their vestigial grasslands interfere with our ‘system’.

We must degrade our waterways, air and soil with the effluent of modern agriculture, because it is most ‘efficient’.

We must purchase and plant the output of centralized biotechnology companies, because that is more ‘efficient’ than following a farmer’s curiosity, drive and wherewithal to breed seed suited to our local landscapes and cultures.

We should be grateful for the plentiful food thus produced, even if we observe increasing obesity diabetes, and malnutrition even among the ‘well-fed’.

We must be grateful for this ‘cheap’ food.

We must endorse these mandates of modern agriculture, while asserting that we are salt of the earth, and that we deserve to maintain our ‘way of life’ even as our food system degrades everyone else’s

If we choose to reject these mandates of ‘modern’ agriculture and farm differently, eat differently, vote differently, then we are quaint, callous, elitist and irrelevant.

We must feed the world, now seven billion, soon nine, then twelve, then what?

I am a farmer/ I am a citizen, and ‘we’ are telling us:

We are indeed grateful for the abundance, ingenuity and hard work that has brought us all much good food and good fortune, and it is time we take stock. How many compromises equal ‘modern’?

It is not our job to fill the Petri dish to bursting point.

The earth is our matrix and regulator. Neither trade associations, nor insurance companies, nor governments, nor universities, nor corporations, nor stock markets, nor our neighbors will superceed its natural systems’ ultimate grasp.

Perhaps some of us are too different to fit the rhythm of modern agriculture---too small, too poor, too new, too foreign, too female, too contrary, too dry, too wet, too close to the land?

Perhaps it is our job to lead the colony to pause, to feed our hearts and our brains, not just our bellies and our banks.

Efficient? Cheap? Robust? Equitable? Durable?

Farmers, of all people, could be the most qualified to recognize and explain that the current practices and trajectories take us to a place we cannot afford, and that we can scarcely want. That is, if we would speak our minds.

Pink slime is only the most recent manifestation, at the output end, of a more deep-seated, long-brewing slurry at the heart of American agriculture. This critique of the half-century-old corn-soybean-feedlot-dominated regime of American agriculture is not an attack on farmers, but is rather a plea to farmers, to awaken to our own complicity in, and our own power to change, the very system that we have allowed to compromise our values, our status, our land, and our futures. Pervasive propaganda notwithstanding, it does not have to be this way, because it cannot continue to be this way.

Have we entered Alice’s rabbit hole, where governors defend pink-slime manufacture for its job creation, even as the numbers of farmers, ranchers and cows continue to dwindle; where Farm Bureau policies perpetuate the dominance of a continental corn desert, even as their roadside posters invoke bucolic red barns and ranchers with calves-in-their-arms; where Monsanto patents life forms and prosecutes farmers, even as it bankrolls a $30 million dollar PR campaign to resurrect agriculture’s sullied reputation?

We have watched and sometimes profited in recent decades as the complex maze of subsidies, lobbies, markets, revolving doors and ignorance have rendered our legislative, executive and judicial branches impotent to find a path out. Consumers are trying to peer down the rabbit hole; scientists are tweaking the dials and reporting some news, but farmers, especially farmers, can and must blast open the portals and reclaim.

Becky Weed is co-owner of Thirteen Mile Farm in southwest Montana. Thirteen Mile runs a small wool mill and is currently revising its long-term sheep operation, collaborating with a young farmer to add vegetables to its lamb and wool marketing. Weed has worked on her own place and with others to raise livestock while coexisting with native carnivores. www.lambandwool.com/