Watershed Media Launches "Reality Check” Communication Tool

[slideshowck id=3275]

Reality Check is a flexible graphic design tool to help organizations advocate against the incursion of large-scale factory farms in their communities.

Each year, the agribusiness industry spends tens of millions of dollars to spin their own stories about the realities of industrial farming. Seven states have passed Whistle Blower suppression legislation — also known as “Ag-gag” laws — that attempt to criminalize the investigation and documentation of day-to-day activities on industrial farms. “Right to Farm” laws have been introduced in nearly 20 states to further shield agriculture from regulations applicable to industrial activities.

Reality Check pairs on-the-ground photos and descriptions with ag industry terminology. Achieving transparency around the true impacts of industrial livestock production is essential to changing the way we produce food and protect the land, rural communities, animal welfare and public health.

Reality Check uses copyright approved photos that can be printed in a variety of formats:

- large-scale posters for exhibit presentation at conferences;

- post cards with information specific to your campaign;

- simple graphics for social media outreach.

We are always on the hunt for appropriate terms and powerful, well-composed images!

We would like to work with your organization so that one day in the future, this pollutive, highly divisive, and unsustainable model of food production will be a thing of the past.

Contact us here.

Watershed Media Produces 2016 California Food and Agriculture Legislation Tracker

For the third consecutive year, Watershed Media worked with Roots of Change (ROC) and the California Food Policy Council (CAFPC) to produce its annual report. The statewide group, that consists of 27 separate councils, tracks bills related to food and agriculture as they make their way through the legislative process. A Policy Work Group votes on which bills to track, renders insightful analysis, and reports the voting records of each member of the state Senate and Assembly. The result is an important document that presents an annual snap shot of policy changes and challenges in the nation’s most populous and most agriculturally productive state.

For the third consecutive year, Watershed Media worked with Roots of Change (ROC) and the California Food Policy Council (CAFPC) to produce its annual report. The statewide group, that consists of 27 separate councils, tracks bills related to food and agriculture as they make their way through the legislative process. A Policy Work Group votes on which bills to track, renders insightful analysis, and reports the voting records of each member of the state Senate and Assembly. The result is an important document that presents an annual snap shot of policy changes and challenges in the nation’s most populous and most agriculturally productive state.

Watershed Media spent two months working along side ROC's intrepid leader Michael Dimock and the writing committee, a dynamic process that required multiple rounds of editing and contributions from many members. Last year's “Food and Agriculture Index” was revised with powerful data points to explain the urgency behind changing policies to address critical issues, from water use, to poverty to climate change. Watershed Media co-founder Roberto Carra's masterful graphic design shines on every page of the report.

“Speaking with a unified voice is not an easy task for a group as diverse as we are," says Dimock, author of the introduction. "Watershed Media adds a depth and skill at helping stakeholders with many different goals and points of view agree on a common language that is both written and visual. Once again we were able to achieve a communication approach and voice that become more important than any individual’s or organization’s agenda.”

Dimock continues: “Because of the careful attention to every aspect of this report, we hope that more citizens and policy makers will spend more time with it and in the process increase their commitments to food systems policy change.”

Download:

Watershed Media Produces 2015 Report on California Food and Farming Legislation

For the second consecutive year, Watershed Media worked with Roots of Change and the California Food Policy Council (CAFPC) to produce its annual report. The statewide group, that consists of 29 separate councils, tracks bills related to food and agriculture as they make their way through the legislative process. Working committees decide on which bills to track, render insightful analysis, and report the voting records of each member of the state Senate and Assembly. While not a report card per se, it is an important document that presents an annual snap shot of policy changes and challenges in the nation’s most populous and most agriculturally productive state.

This year Watershed Media was far more involved in the CAFPC reporting process. Dan Imhoff worked along side the writing committee, a dynamic group process that required multiple rounds of editing and contributions from members. He also introduced the concept of a “Food and Farming Index,” as a way of using powerful data points to explain the urgency behind changing policies to address critical issues, from water use, to poverty and climate change. In addition to a smart design for the report itself, Roberto Carra created a logo to give CAFPC a strong graphic identity.

“Watershed Media showed both a depth and skill at helping a diverse group of stakeholders agree on common language in clarifying goals and intentions,” says Michael Dimock,” director of Roots of Change and author of the report’s introduction. “The expertise and well framed suggestions from Dan and his team helped us achieve a communication approach and voice that became more important than any individual’s or organization’s agenda.”

Dimock continues: “Because of the punchy design, addition of the index, direct language, our hope is that more citizens and policy makers will spend more time with the report and in the process increase their commitment to food systems policy change.”

Download a copy of the 2015 CAFPC Report here.

In Memoriam — Deep Ecology Champion and Watershed Media Collaborator, Douglas Tompkins

On December 8, 2015, the world lost one of the greatest conservation champions of this generation when Douglas Tompkins died unexpectedly in a kayak accident in southern Chile. He was 72 years old. Doug led an extraordinary life, first as an entrepreneur and founder and co-founder of businesses such as the North Face and Esprit, and for the past 25 years as a devoted conservationist, ecosystem restorer, adventurer and environmental activist. He was also my father-in-law.

Watershed Media co-founder, Roberto Carra, and I both met and worked with Doug at Esprit, a global fashion company that became a major innovator in design as well as workplace and social engagement. Esprit was the first global company I know of, for example, to ban cigarette smoking from its offices, stores and facilities. The in-house cafe was subsidized, there were sponsored daily fitness classes and yearly river trips. They took the lead on AIDS funding, employee volunteerism, and eco auditing. In the five years Roberto and I worked closely together there, Esprit pioneered the research and production of Ecollection, a clothing line solely dedicated to solutions such as organic cotton, low impact dyes and finishes, artisanal accessories and other developments still considered leading edge today.

Doug Tompkins sold his shares of the brand he helped create in 1991 and moved to a remote part of Chile, a country he had been exploring as a pilot, rock climber and kayaker for many decades. With this life change, he also shifted his powers as a communicator to the ideas of Deep Ecology. Originally conceived by Norwegian author Arne Naess, this philosophy holds that the environmental crises facing humanity require us to address fundamental root causes such as industrialization, overdevelopment, overconsumption, overpopulation, and biodiversity loss.

These were bold and controversial ideas for an environmental movement often more concerned with incremental progress than fundamental change. In an effort to catapult this discussion to the broader society, Doug launched a series of large format picture books, much in the spirit of David Brower's activist publications with Sierra Club Books decades earlier. He set up and funded the Foundation for Deep Ecology and began the production of hard hitting titles that combined essays with powerful photographs, often employing editorial devices more common in magazines and advertising than book publishing. Grassroots campaigns were linked to these books to draw media attention and build public awareness. The list of titles is impressive, including Clearcut: The Tragedy of Industrial Forestry, Fatal Harvest: The Tragedy of Industrial Agriculture, Plundering Appalachia, and at least two dozen more.

Watershed Media co-published CAFO: The Tragedy of Industrial Animal Factories as part of the Foundation for Deep Ecology series. Many years in the making, it debuted in 2010, featuring more than 450 photographs and over 30 wide ranging essays. Winner of the Nautilus Prize for Investigative Reporting, it remains the most damning publication about the wrongs of confinement animal agriculture to date. Watershed Media was also a co-publisher of Energy: Overdevelopment and the Delusion of Endless Growth, in 2012. When we produced Farming with the Wild in 2003, a book that highlighted farming models that combined agriculture and habitat connectivity, the Foundation for Deep Ecology became our primary supporter. At a time when the foundation community was keenly pursuing market-based solutions, Doug insisted that biodiversity protection had to be the core of any project he supported.

"Doug had a very strong sense of visual style," remembers Italian born art director and photographer, Roberto Carra. "From the aesthetic viewpoint, he was almost always right." As the owner of the first manifestation of the North Face, an outdoor mountaineering shop located in San Francisco, Doug visited the studio of Ansel Adams in Big Sur in hopes of securing evocative images of the California wilderness for his retail space. (His trip was successful!) Throughout his life Doug was constantly behind a camera himself, shooting pictures not only to document his life, but to direct ecological farming projects, land restoration, architecture and the many other endeavors he took on.

He loved photo editing but was an equally voracious reader and completely dedicated to making a lasting contribution to important contemporary discourse. Yet communication was but one facet of this extremely productive individual's life. Over the past 25 years, Doug and his wife Kristine Tompkins privately purchased over 2.2 million acres of land in Chile and Argentina and are in the process of creating 5 national parks and expanding others, essentially importing the long standing American tradition of conservation philanthropy to these countries. They also initiated "rewilding" efforts to reintroduce species such as the jaguar and anteater to their former ranges in northern Argentina.

"For Doug, no detail was small," remembers Roberto. These are important words for communicators to remember. And they are exceptional considering he held such a large view of the world and had the ability to build organizations and inspire the team work necessary to accomplish his visions.

Doug was amazingly focused. He was enormously talented and inspired. As a collaborator, he was extremely demanding and occasionally overbearing, but his standards were lofty, particularly those he kept for himself. He died among friends doing what he loved amidst the creaturely world he dedicated all his resources and energy to protect.

He will be sorely missed. The conservation efforts he inspired will live on.

Download a PDF of an article I wrote for the 2001 publication The World and the Wild: Expanding Wilderness Conservation Beyond its American Roots, by David Rothenburg and Marta Ulvaeus.

Learn more about Doug and Kristine Tompkins' work here.

"Unless we learn to share the Earth with all the other creatures on the planet, our own days are numbered. . . . We need to teach our children that each person must pay his or her “rent” for living on the planet, and that means demanding of our governments to make biodiversity conservation a priority. The primary means to this end will be more protected areas and, best of all, more national parks."

—Doug Tompkins

Photo by Beth Wald.

True Cost Agriculture Report Targets World Bank Loan Programs

Washington DC, September 15, 2015 — A report released by Watershed Media and Foundation Earth urges World Bank leaders to revamp policies that oversee more than $10 billion in agriculture loans and grants each year. At the root of their analysis is the need for new financial frameworks that address “externalities”—earth and health damaging impacts of economic activities that currently don’t show up on profit and loss sheets or loan applications.

Washington DC, September 15, 2015 — A report released by Watershed Media and Foundation Earth urges World Bank leaders to revamp policies that oversee more than $10 billion in agriculture loans and grants each year. At the root of their analysis is the need for new financial frameworks that address “externalities”—earth and health damaging impacts of economic activities that currently don’t show up on profit and loss sheets or loan applications.

“In the face of a rapidly overheating climate, collapsing fisheries, degraded soil, depleted water resources, vanishing species, and other challenges directly related to agriculture, we can no longer afford to pursue a flawed accounting system,” write Dan Imhoff (Watershed Media) and Randy Hayes (Foundation Earth), authors of the report.

They recommend a new True Cost Accounting approach designed to fund Biosphere Smart Agriculture projects that produce the healthiest food with the least environmental impacts for the long-term security of target communities.

Among the key goals of the World Bank’s growing agriculture program are raising income levels and alleviating poverty among the world’s poorest populations while also addressing climate change. Agriculture contributes 25 to 30 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions. It’s also one of the economic sectors most directly affected by rising temperatures, searing droughts and violent flooding.

According to the new report, the World Bank should focus its essential financial assets toward growing a global agroecology movement in order to fight poverty and turn back the earth warming impacts of food production. This means shifting away from the large-scale industrial mindset that has dominated the Bank’s development philosophies for decades and investing in a new generation of smaller scale, ecologically sustainable, information intensive farming systems.

As part of this research, the Switzerland based Millennium Institute was commissioned to study potential outcome scenarios for a current World Bank loan. Using their T-21 modeling program, they analyzed the on-the-ground outcomes of an $86 million loan to Senegal, primarily for bringing new irrigation systems to two regions of the West African nation. Millennium’s study determined that, while new irrigation projects will help raise a number of Senegalese out of poverty, the loan would dramatically improve livelihoods if directed toward a community-based agroecology initiative.

At the April 2015 annual meetings in Washignton DC, World Bank President Jim Yong Kim declared that the World Bank needs to become part of the solution of rethinking food in developing countries.

“We hope that this report will be essential reading for that rethinking process,” says Foundation Earth President Randy Hayes.

Download the full report here.

PBS Farm Bill documentary features Dan Imhoff and Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack

From the Founding Farmers to the modern Farm Bill, what has 200 years of progress brought to the table? More food at lower prices for sure, but also food fights over the environment, hunger, nutrition, and waste. In this closing episode of the 13-part PBS series Food Forward TV, Watershed Media co-founder Dan Imhoff, along with politicians, policy watchdogs and food experts take viewers on a personal tour through the history of food and agriculture in America. There’s an entry point for everyone in the conversation about how we feed ourselves.

Watershed Media Designs 2014 Legislative Report

In late 2014, the advocacy group Roots of Change hired Watershed Media to produce its annual report on California''s food and agriculture bills. Changing the food system is currently a hot topic in California politics. Last year's proposed bills ranged from carbon payments to nutrition assistance to fair labor regulations and many other relevant issues. The state already has 25 food policy councils in cities large and small forming a united front for a more ecologically and socially responsive approach to agriculture. Watershed Media's job was to make the California Food Policy Council (CAFPC) technical report come alive on the page. We created a "word cloud" cover as well as a series of icons to illustrate the values and principles the CAFPC stands for. These went along with a chart detailing how the state's entire legislature voted on a series of bills related to the food and farming issues. The report has garnered a lot of attention, at least some of which comes from making technical information accessible and visually dynamic— one of Watershed Media's specialties.

Report Download

Hermannsdorf: Symbiotic Farming

Snow is falling as the plane touches down at Munich airport. By the time we arrive in Hermannsdorf, an hour’s drive, the forests and rolling hills of the Upper Bavarian countryside are pillowed in a few inches of white powder. My wife, Quincey, and I are on a mid-winter European junket. We’ve tagged along with her father, Doug Tompkins, to visit the farm of Karl-Ludwig Schweisfurth, one of Germany’s (and the world’s) leaders in the sustainable food movement.

We start our tour at the Schweisfurth home, a delightful cottage decorated with all manner of livestock-inspired artwork. Karl-Ludwig is a tall, solid-boned, man with a mane of white hair and horn-rimmed spectacles. Now in his mid-80s, Karl-Ludwig grew the family business, Herta, into one of Europe’s largest meat processing corporations. He even based its expanding production lines on Oscar Mayer assembly operations, where his father sent him as a young man to study American innovation. “I am a butcher,” he says, deprecatingly, acknowledging the role and trade that life have given him.

After three decades in the meat packing business, however, Schweisfurth realized that the perpetual need for growth and ever-increasing disassembly line speeds came at too high a cost. He saw animal welfare, work conditions, health of the environment, food quality, and personal values plummeting as humans became further and further disconnected from the basic tasks of food production. In 1984, at age 54, he sold the business to start over again with his two sons. His career as a butcher wasn’t at an end. Rather, it became one skill among a larger set that requires farming, animal husbandry, meat processing, and retailing. The revamped family business soon included an inn, organic farm, restaurant, brewery, and bakery. It became a hub for local employment and the purchase of regionally produced organic grains and other ingredients.

Around his kitchen table, Karl Ludwig explains his concept of “symbiotic agriculture.” For more than two decades, he has been experimenting with raising different species of livestock on the same pastures using various mobile structures. The pigs protect the chickens from predators. The chickens eat parasites that might potentially sicken the pigs. The free ranging animals’ manure returns vital nutrients to the soil as they graze. Hundreds of acres of fields and livestock pastures at the farm, officially called “HermannsdorferLandwerkstätten,” are planted with various crops that provide forage for the animals or feed that can be stored for the winter. The farm’s workers are always striving for the best rotations of pasture crops to prevent pests from becoming too established, maintain healthy soil, and keep meat flavor as high as possible. On the kitchen table is a wooden model of a mobile group housing structure. I take off the wooden roof to inspect. The pigs’ quarters are downstairs. Poultry enter around the back and roost upstairs.

Finally it’s time to walk. We find plenty of animals out on the snowy landscape. Bavarian-styled chicken tractors house birds for both meat and eggs, active out in the cold winter day. Pigs are kept in permanent barns, as well as in smaller groups with simple wooden structures out in the fields. The barns have roomy outside stalls full of straw and covered internal stalls for feeding and weather protection. Families are raised together for their entire lives to honor the social hierarchies they develop at birth. Karl Ludwig delights in explaining the natural conditions in which the animals are raised. Below the barn, he points to a methane digester, a covered circular tank about the size of a yurt. There animal waste from the pig barns is processed. It generates electricity from captured methane gas. Compost for the farming operation is made from the remaining solid waste.

When we enter the slaughter plant, Karl Ludwig describes it as “the best plant I have ever designed.” It is white tiled, very clean. Chain mesh gloves and white aprons hang in orderly fashion. The animals are raised right on the farm and are moved to holding pens close by prior to slaughter. There is no long distance transportation involved that heightens stress in animals. The slaughter room and butchering operation are completely separated, he explains, so that no animal has a sense of imminent death. “I realize that in order to process animals I must kill them,” he says. “So I want to make both their lives and their deaths as compassionate as possible.” On a given week, 100 pigs, 20 bulls, and 100 sheep are killed, butchered and begin the curing and processing stage.

We tour a curing facility, a hall with a series of brick-lined rooms where meats are aged. The smell is sweet, sour and pungent. One room is filled with hanging hams that seem to be the German equivalent of Italian prosciutto or Spanish Serrano. Another room contains many racks of salamis. The air is peppery. The rooms have been cleverly designed using the thermal mass of the hill that the building abuts to provide optimum humidity and temperature controls with the least amount of energy.

In a processing kitchen we find large mixing machines for making sausages. Each stainless steel bowl could easily hold a person. Two ovens are presently occupied in the smoke curing of pork bellies. We see Karl-Ludwig’s guidance everywhere. The organizing principle, from start to finish is quality: for animals, workers, the environment, and eaters.

At last, we sit down to break bread. It is no wonder that the operation at Hermannsdorf is a popular tourist destination, with its beautiful restaurant and modern organic grocery. Karl-Ludwig’s family joins us at the table, a wide open floor plan with high ceilings and exposed wooden rafters, reclaimed from the former building, which was a mill. In addition to the restaurant they have a micro-brewery and a bakery. Both use ingredients from the farm and purchase grains, hops, and malt from regional farmers. We taste a goat cheese appetizer that is light, tangy and creamy. Spread on chewy dark German bread, it combines perfectly with a stein of the family Schwinebrau brown ale. This is followed by sautéd fennel and leeks, a crispy potato pancake, and a roast of veal that is shimmery and pink with a clean robust flavor. A lager beer, the paler brother of the ale, accompanies this main course. Karl-Ludwig carves the meat from his seat at the head of the table, generously passing samples to customers at the next table.

At the meal’s end, we present Karl Ludwig with a copy of the photo book, CAFO: The Tragedy of Industrial Animal Factories, that Doug Tompkins (Foundation for Deep Ecology) and I (Watershed Media) co-produced. He looks at the grisly photo on the front cover. It’s a dark scene inside an industrial hog facility. He points to me, shakes his head and with sad eyes asks, “You made this book?” I nod my head yes. “I finally decided to get out of the industrial meat business when I went inside one of these,” he says. He begins flipping through the large photographs of animal processing, waste lagoons, feedlots, and then puts it aside, knowing all too viscerally the heavy content featured in the book.

We have landed in one of the epicenters of the global healthy food movement. It’s a social current that is slowly sweeping the entire planet. I’ve been lucky enough to visit other places where science, art, land stewardship and food production combine at such profound levels. I see as this as our modern renaissance. Hermannsdorf is on the scale of the Prince of Wales’ efforts at the Duchy Home Farm in the English Cottswalds, Doug Tompkins’ pioneering farmscaping at Laguna Blanca in Argentina, and Wes Jackson’s visionary perennial polyculture at the Land Institute in Kansas.

Karl Ludwig is convinced that this approach to sustainably produced meat and grains—“symbiotic agriculture”—is not just a wealthy man’s hobby, not just a passing fad. It is the future that agriculture must somehow become. His son calls it “retro innovation,” the combination of land management and husbandry practices of the pre-petrochemical and pre-animal antibiotic past, with the understanding of ecological systems and small-scale agricultural technology of today. This is information rich, systems thinking: finding ways for the farming to fit the land, and for the land to feed the animals.

A day’s visit is not enough. We need more time to explore. I have dozens more questions. But we must be on the road to our next destination, and leave, having tasted, experienced, and fully sensed Hermannsdorf, a lighthouse to the world of food and farming.

Links:

Doug Tompkins’ pioneering farmscaping at Laguna Blanca inArgentina

Message to Congress: Stop Monkeying Around with Conservation Budgets

When most Americans think of the agencies in charge of nature conservation, the Department of the Interior or the National Park Service likely spring to mind. They don’t think of the Department of Agriculture, which allocates nearly $4 billion per year to land conservation in its Farm Bill.

This summer the House and Senate are rewriting the Farm Bill, which Congress last year kicked down the road. The 10-year price tag will total nearly a trillion dollars, funding food stamps, agribusiness subsidies, conservation, and research. Budget cutters are searching for billions of dollars to slash, and Farm Bill conservation programs, once again, seem vulnerable.

This is real cause for concern. Established in response to the overplowing that led to the Dust Bowl, conservation programs are intended to compensate landowners for vital work that the free market does not value: soil protection, wetland and grassland preservation, water filtration, pesticide and fertilizer reduction, carbon sequestration. Safeguarding natural resources in a time of rising temperatures and more violent weather events are crucial investments in public health and national security.

Of all agriculturally-related federal spending, conservation programs can offer the public the biggest return for the taxpayer dollar. They can expand the availability of organic and pasture-raised foods, help farmers reduce runoff that harms public waterways, promote soil-enhancing practices like cover cropping and field rotations, and protect farmland and wildlands for future generations.

Unfortunately, most members of Congress, including many influential members of the House and Senate Agricultural Committees, don’t understand the devastating toll that six decades of Farm Bill subsidized factory farming methods has taken on the land—or the power of conservation programs to reverse them.

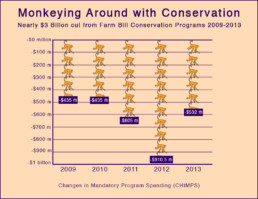

Adding insult to injury, those conservation programs that do exist rarely get the money they are promised when Farm Bills are passed. Legislators make a big deal about how the Farm Bill protects the environment. But whenever budget appropriators need savings, conservation programs are the first on the chopping block. There’s a term for this: Changes in Mandatory Program Spending, or CHIMPS.

Over the last five years, Conservation budgets have been CHIMPed by more than $3 billion, with nearly $2 billion in cuts between 2011 and 2013 alone. That’s not because there’s no demand for the programs. Three out of four applications are turned away for lack of funding.

Even common sense on-farm stewardship practices that were historically required of farm subsidy recipients are disappearing from the Farm Bill. Take taxpayer funded crop insurance. Over the past five years, subsidized crop insurance has become farmers’ preferred source of taxpayer assistance. Crop insurance policies currently come with no land conservation requirements. Because of this, they are actually causing a massive amount of previously protected land to be plowed up. Farmers anxious to cash in on record crop prices no longer have to worry about yields when taxpayer programs guarantee them against losses. Across the Great Plains, corn and soybeans are being planted on millions of acres of erodible lands that were previously deemed marginal and formerly protected through the Conservation Reserve Program. Scientists fear another Dust Bowl is in the making.

“Congress right now has the ability and responsibility to transform the Conservation Title for the next 10 years,” says Oregon Representative Earl Blumenauer. In May, Blumenauer introduced HR 1890, the “Balancing Food, Farms and Environment Act of 2013.” The bill is just one of many intended to strengthen conservation efforts into the House and Senate Farm Bills, which should come to floor votes this summer. A Coburn-Durban amendment is aimed at imposing income thresholds on crop insurance for the largest farmers. HR 1890 would provide more money for to protect land in permanent easements and reward farmers for carbon sequestration. Chellie Pingree of Maine introduced an amendment to expand supports to organic farmers.

In a political landscape hostile to environmental protection, agricultural lobbies have for decades found ways to pilfer conservation budgets to help boost crop and livestock production. Over the last ten years alone, according to the Environmental Working Group, two billion dollars in the Environmental Quality Incentives Program have been diverted to pay for the hard costs of establishing waste containment structures for concentrated animal feeding operations, laying pipe for irrigation in arid regions, and draining wetlands.

Like the Olympic Games, the renewal of the Farm Bill only comes around every four to five years. It offers the opportunity for Americans to invest in the long-term health of farmlands and the countryside. But time may be running out.

Could this year be a turning point for Farm Bill conservation reforms, like the 1985 and 1990 Farm Bills, which established far-reaching efforts to protect grasslands and wetlands across the heartland?

The Factory Farms of Lenawee County

Eastern, Michigan, March 2013 — Rolling across North Carolina, Indiana, Illinois, Washington, California, and today, eastern Michigan, I’ve seen first-hand the impacts of industrial dairy, poultry, and hog factories on rural communities. I admire the people who fight back against the invasion of factory farms. I seek them out, trying to see the land from their eyes. But no matter how many times I experience it, I still find unpalatable a business model that’s based on marginalizing animal welfare and polluting your neighbors’ air, land, water and quality of life in the name of profit and cheap food.

Eastern, Michigan, March 2013 — Rolling across North Carolina, Indiana, Illinois, Washington, California, and today, eastern Michigan, I’ve seen first-hand the impacts of industrial dairy, poultry, and hog factories on rural communities. I admire the people who fight back against the invasion of factory farms. I seek them out, trying to see the land from their eyes. But no matter how many times I experience it, I still find unpalatable a business model that’s based on marginalizing animal welfare and polluting your neighbors’ air, land, water and quality of life in the name of profit and cheap food.

Lynn and Dean Henning are guiding me on a tour of the CAFOs of Lenawee County. It’s a cold morning in early spring. The landscape is leached of color. The ponds are thick with ice. An occasional snowflake flutters from wooly clouds.

“When they spray manure in the winter, sometimes you can see it hanging frozen from the irrigation booms,” says Lynn from the back seat. “We call them ‘poopsicles.’”

“What’s it like here when spring arrives?” I ask, imagining a painterly transformation of the countryside with grass, foliage, blossoms, songbirds.

“Springtime smells really bad,” she answers.

Dean is driving. He is silver haired, in his late fifties. He has cut back on farm work since suffering a heart attack and a subsequent quadruple by-pass surgery a few years ago. We travel by “Henning Hwy.,” named after his grandfather, the first homeowner to bring electricity to the neighborhood. Dean still farms a few hundred acres of corn and soybeans, manages a few hundred acres of forestland, and maintains a massive garden that produces a prodigious quantities of tomatoes, sweet corn, and other heirloom vegetables for family and friends.

I already know Lynn Henning as the anti-CAFO warrior with waves of white hair who won the prestigious 2010 Goldman Environmental Prize. Lynn and I have met a few times as fellow conference speakers. She and Dean have been kind enough to let me tag along on one of their thrice-weekly surveys of creeks and drainages, scouting for discharges from the dozen or so dairy CAFOs spaced at five-mile intervals around their area.

With its vegetable, tree fruit, grain and livestock production, Michigan boasts the country’s most diverse agricultural output next to California. But Lenawee County is corn and soybean country. Its fields follow the rolling contours of the land. Broad fields are interwoven between small belts of trees and complex drainages that carve through the sloping lands, sometimes flattening out in low-lying wetlands. This is precisely the challenge of concentrating livestock in this area: how to keep the waste from running off fields into the many surface and underground drainage systems that feed creeks, streams, river arteries and eventually flow into the now mightily polluted Lake Erie.

Our first stop is Hartland Farms, a Concentrated Animal Feeding Operation (CAFO) with 1,000 dairy cows and 2,000 acres of cropland. As Lynn rattles off the complicated web of partnerships that make up its ownership, it becomes immediately obvious to me why a CAFO is so aptly referred to as a “factory farm.” The buildings are sheathed in steel. Cows are nowhere to be seen. They are housed inside by the hundreds in linear stalls, moving only to lie down or take their turns at the electronic milking parlor. Waste exits one end of the facility the way a vertical smokestack might release pollution skyward. Instead of smoke, the CAFO pipe spews concentrated liquid animal waste—rich in nitrogen, phosphorous, ammonia and other chemicals and laden with bacteria such as fecal coliform and E. coli. The waste is temporarily stored in nearby holding lagoons that are bermed into ponds as long as football fields and deep enough to contain millions of gallons of waste. Waste off-gasses into the atmosphere that floats across the surrounding community. Waste is spread on nearby fields or pumped directly into underground irrigation pipes beneath fields.

“They plaster it on 8 inches thick and spray right up to the roadsides,” says Lynn.

“In liquid form,” adds Dean, “it doesn’t stay on the ground too long.”

The image of 100-acre fields smeared with CAFO manure more than a half a foot deep is nauseating. In fact, I can see the brown green shadow from a recent ground application glistening between rows of stubble left from last year’s corn harvest.

Dean and Lynn make the rounds of potential discharge sites. A drain can be a simple grass-lined gulley that moves through the low point of a field. It could be a culvert that spans beneath a road. Eventually the water moves onto successively larger waterways, like the South Branch of the River Raisin.

In order to monitor what is happening to their community, the Hennings, along with other members of the Environmentally Concerned Citizens of South Central Michigan, have become citizen scientists. Armed with a variety of hand-held devices, volunteers can monitor for nutrients, chemicals, bacteria, antibiotics and biological oxygen demand. Samples are sent to a lab if results indicate potentially dangerous contaminants. Any alarming findings are officially reported to the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality.

Rural agricultural conflicts like these are not just the result of too many humans coming up against too few resources. These fights have been going on for a very long time. Way back in 1610, English landholder William Aldred claimed that his neighbor, Thomas Benton’s pig sty, was sited too close to his home. Aldred argued that the livestock operation was violating his rights as a community member. Upon hearing the case, King Charles I’s court ruled in Aldred’s favor, deciding that no one has “the right to right to maintain a structure upon his own land, which, by reason of disgusting smells, loud or unusual noises, thick smoke, noxious vapors, the jarring of machinery, or the unwarrantable collection of flies, renders the occupancy of adjoining property dangerous, intolerable, or even uncomfortable to its tenants." In other words, it’s against common law to stink up or foul the neighborhood.

Four centuries later, it is still to the courts where citizens must turn when their air, water, and health are violated by intensive concentrations of animals.

We make a stop at what looks like a recently constructed CAFO facility. There are four white hangar-like barns. Sandwiched between the four barns is a fancier brick building that must serve as the main office. But something is amiss. There are no trucks in the lot. There’s no one around at all. The mailbox is tilted at a funny angle. The place is abandoned. Apparently, the CAFO went belly up. It’s been taken over by the bank and is for sale.

Factory farms, I learn, are a relatively new phenomenon in Lenawee County. The first mega-dairy arrived in 1999 as the Hudson area became a target of the Vreba-Hoff Dairy Development syndicate. This family, with Dutch origins, is now legendary across the Midwest for fabricating an elaborate Ponzi scheme that started over 90 mega-dairies, mainly with investments from European families they conned into coming to America. Facilities were often never completed or were simply unprofitable. Environmental violations were routine. Even as dairies failed, Vreba-Hoff continued to attract more investors, expanding further into rural communities. Many investors were forced into bankruptcy. Creditors lost millions. The CAFO conmen took the money and skipped town.

“Small town drama,” says Lynn.

Indeed. The more you look behind the curtain, this CAFO model becomes a serious shell game. Pack as many animals on a particular property as an agency will authorize with a pollution permit (if the agencies even require one.) Convince local governments to build new roads and other infrastructure. Rake in hundreds of thousands in US Department of Agriculture subsidies to help pay for waste management costs, and on top of that, take advantage of feed subsidies, taxpayer supported crop insurance and disaster payments for your croplands. Degrade the health of the neighborhood with waste emissions and stench, slowly driving homeowners out, then buy up their devalued properties in the process.

“They use manure as a weapon,” says Dean.

We are passing through the half-boarded up farming town of Medina. It’s a victim of what can only be described as economic undevelopment.

“Why don’t people fight back?” I ask.

“People are afraid to pick fights,” says Lynn. “It’s like the town in A Civil Action. People have lived here forever. Many are convinced that they need this system, that they’ll earn money renting their land to the CAFOs for field applications.”

“Even when that waste damages their soil and lowers their yields,” adds Dean.

“People will drop a note in the mailbox or take me aside every once in a while and thank me for speaking out,” says Lynn.

I think about the twisted and somewhat tragic logic at work: an unhealthy food production system that people somehow accept as inevitable. A system where many of the real costs of production—effects on human health, impacts on shared water resources, basic costs of feed and waste management—are passed off on local communities and federal taxpayers. I ask Lynn and Dean to talk about the words and terminology which industry uses to describe these events I am seeing.

“They always speak of ‘odor,” says Dean, “never of toxic pollution.”

“Waste runoff and lagoon overflows after heavy rains is always ‘storm water,” says Lynn.

“Waste running into the creeks is a ‘discharge,” says Dean.

“Lagoon waste spread across the farm fields is ‘sediment,” says Lynn. “But it’s never dry and it’s not sediment. And underground pipes that drain straight into the creeks are ‘sub-irrigation systems.’”

We stop at an infamous site where a 20-acre wetland was filled with CAFO waste a few years back.

“The EPA was here to see it,” says Lynn.

I begin to fear that in my zeal to document this tour with photos I’ve been breathing nasty air. It’s no doubt on my boots and clothes and perhaps in my respiratory system.

“What if you could buy up one of these defunct CAFOs and turn it into a demonstration farm for a new kind of pasture-based, healthy agriculture?” I ask.

“I wish we could,” says Lynn.

Dean describes a farm. “A 640-acre section is a square mile,” he says. “You would want to keep at least 160 acres in woodland. The rest could be fenced off so that fields could be rotated between pasture and row crops. At two acres per cow, you could have a diversified farming operation,” he says. “This model could be very effective on smaller operations.”

I can almost imagine a new era of integrated agriculture catching on in Lenawee County. As someone once said, it’s hope that makes us human.