Hermannsdorf: Symbiotic Farming

Snow is falling as the plane touches down at Munich airport. By the time we arrive in Hermannsdorf, an hour’s drive, the forests and rolling hills of the Upper Bavarian countryside are pillowed in a few inches of white powder. My wife, Quincey, and I are on a mid-winter European junket. We’ve tagged along with her father, Doug Tompkins, to visit the farm of Karl-Ludwig Schweisfurth, one of Germany’s (and the world’s) leaders in the sustainable food movement.

We start our tour at the Schweisfurth home, a delightful cottage decorated with all manner of livestock-inspired artwork. Karl-Ludwig is a tall, solid-boned, man with a mane of white hair and horn-rimmed spectacles. Now in his mid-80s, Karl-Ludwig grew the family business, Herta, into one of Europe’s largest meat processing corporations. He even based its expanding production lines on Oscar Mayer assembly operations, where his father sent him as a young man to study American innovation. “I am a butcher,” he says, deprecatingly, acknowledging the role and trade that life have given him.

After three decades in the meat packing business, however, Schweisfurth realized that the perpetual need for growth and ever-increasing disassembly line speeds came at too high a cost. He saw animal welfare, work conditions, health of the environment, food quality, and personal values plummeting as humans became further and further disconnected from the basic tasks of food production. In 1984, at age 54, he sold the business to start over again with his two sons. His career as a butcher wasn’t at an end. Rather, it became one skill among a larger set that requires farming, animal husbandry, meat processing, and retailing. The revamped family business soon included an inn, organic farm, restaurant, brewery, and bakery. It became a hub for local employment and the purchase of regionally produced organic grains and other ingredients.

Around his kitchen table, Karl Ludwig explains his concept of “symbiotic agriculture.” For more than two decades, he has been experimenting with raising different species of livestock on the same pastures using various mobile structures. The pigs protect the chickens from predators. The chickens eat parasites that might potentially sicken the pigs. The free ranging animals’ manure returns vital nutrients to the soil as they graze. Hundreds of acres of fields and livestock pastures at the farm, officially called “HermannsdorferLandwerkstätten,” are planted with various crops that provide forage for the animals or feed that can be stored for the winter. The farm’s workers are always striving for the best rotations of pasture crops to prevent pests from becoming too established, maintain healthy soil, and keep meat flavor as high as possible. On the kitchen table is a wooden model of a mobile group housing structure. I take off the wooden roof to inspect. The pigs’ quarters are downstairs. Poultry enter around the back and roost upstairs.

Finally it’s time to walk. We find plenty of animals out on the snowy landscape. Bavarian-styled chicken tractors house birds for both meat and eggs, active out in the cold winter day. Pigs are kept in permanent barns, as well as in smaller groups with simple wooden structures out in the fields. The barns have roomy outside stalls full of straw and covered internal stalls for feeding and weather protection. Families are raised together for their entire lives to honor the social hierarchies they develop at birth. Karl Ludwig delights in explaining the natural conditions in which the animals are raised. Below the barn, he points to a methane digester, a covered circular tank about the size of a yurt. There animal waste from the pig barns is processed. It generates electricity from captured methane gas. Compost for the farming operation is made from the remaining solid waste.

When we enter the slaughter plant, Karl Ludwig describes it as “the best plant I have ever designed.” It is white tiled, very clean. Chain mesh gloves and white aprons hang in orderly fashion. The animals are raised right on the farm and are moved to holding pens close by prior to slaughter. There is no long distance transportation involved that heightens stress in animals. The slaughter room and butchering operation are completely separated, he explains, so that no animal has a sense of imminent death. “I realize that in order to process animals I must kill them,” he says. “So I want to make both their lives and their deaths as compassionate as possible.” On a given week, 100 pigs, 20 bulls, and 100 sheep are killed, butchered and begin the curing and processing stage.

We tour a curing facility, a hall with a series of brick-lined rooms where meats are aged. The smell is sweet, sour and pungent. One room is filled with hanging hams that seem to be the German equivalent of Italian prosciutto or Spanish Serrano. Another room contains many racks of salamis. The air is peppery. The rooms have been cleverly designed using the thermal mass of the hill that the building abuts to provide optimum humidity and temperature controls with the least amount of energy.

In a processing kitchen we find large mixing machines for making sausages. Each stainless steel bowl could easily hold a person. Two ovens are presently occupied in the smoke curing of pork bellies. We see Karl-Ludwig’s guidance everywhere. The organizing principle, from start to finish is quality: for animals, workers, the environment, and eaters.

At last, we sit down to break bread. It is no wonder that the operation at Hermannsdorf is a popular tourist destination, with its beautiful restaurant and modern organic grocery. Karl-Ludwig’s family joins us at the table, a wide open floor plan with high ceilings and exposed wooden rafters, reclaimed from the former building, which was a mill. In addition to the restaurant they have a micro-brewery and a bakery. Both use ingredients from the farm and purchase grains, hops, and malt from regional farmers. We taste a goat cheese appetizer that is light, tangy and creamy. Spread on chewy dark German bread, it combines perfectly with a stein of the family Schwinebrau brown ale. This is followed by sautéd fennel and leeks, a crispy potato pancake, and a roast of veal that is shimmery and pink with a clean robust flavor. A lager beer, the paler brother of the ale, accompanies this main course. Karl-Ludwig carves the meat from his seat at the head of the table, generously passing samples to customers at the next table.

At the meal’s end, we present Karl Ludwig with a copy of the photo book, CAFO: The Tragedy of Industrial Animal Factories, that Doug Tompkins (Foundation for Deep Ecology) and I (Watershed Media) co-produced. He looks at the grisly photo on the front cover. It’s a dark scene inside an industrial hog facility. He points to me, shakes his head and with sad eyes asks, “You made this book?” I nod my head yes. “I finally decided to get out of the industrial meat business when I went inside one of these,” he says. He begins flipping through the large photographs of animal processing, waste lagoons, feedlots, and then puts it aside, knowing all too viscerally the heavy content featured in the book.

We have landed in one of the epicenters of the global healthy food movement. It’s a social current that is slowly sweeping the entire planet. I’ve been lucky enough to visit other places where science, art, land stewardship and food production combine at such profound levels. I see as this as our modern renaissance. Hermannsdorf is on the scale of the Prince of Wales’ efforts at the Duchy Home Farm in the English Cottswalds, Doug Tompkins’ pioneering farmscaping at Laguna Blanca in Argentina, and Wes Jackson’s visionary perennial polyculture at the Land Institute in Kansas.

Karl Ludwig is convinced that this approach to sustainably produced meat and grains—“symbiotic agriculture”—is not just a wealthy man’s hobby, not just a passing fad. It is the future that agriculture must somehow become. His son calls it “retro innovation,” the combination of land management and husbandry practices of the pre-petrochemical and pre-animal antibiotic past, with the understanding of ecological systems and small-scale agricultural technology of today. This is information rich, systems thinking: finding ways for the farming to fit the land, and for the land to feed the animals.

A day’s visit is not enough. We need more time to explore. I have dozens more questions. But we must be on the road to our next destination, and leave, having tasted, experienced, and fully sensed Hermannsdorf, a lighthouse to the world of food and farming.

Links:

Doug Tompkins’ pioneering farmscaping at Laguna Blanca inArgentina

Message to Congress: Stop Monkeying Around with Conservation Budgets

When most Americans think of the agencies in charge of nature conservation, the Department of the Interior or the National Park Service likely spring to mind. They don’t think of the Department of Agriculture, which allocates nearly $4 billion per year to land conservation in its Farm Bill.

This summer the House and Senate are rewriting the Farm Bill, which Congress last year kicked down the road. The 10-year price tag will total nearly a trillion dollars, funding food stamps, agribusiness subsidies, conservation, and research. Budget cutters are searching for billions of dollars to slash, and Farm Bill conservation programs, once again, seem vulnerable.

This is real cause for concern. Established in response to the overplowing that led to the Dust Bowl, conservation programs are intended to compensate landowners for vital work that the free market does not value: soil protection, wetland and grassland preservation, water filtration, pesticide and fertilizer reduction, carbon sequestration. Safeguarding natural resources in a time of rising temperatures and more violent weather events are crucial investments in public health and national security.

Of all agriculturally-related federal spending, conservation programs can offer the public the biggest return for the taxpayer dollar. They can expand the availability of organic and pasture-raised foods, help farmers reduce runoff that harms public waterways, promote soil-enhancing practices like cover cropping and field rotations, and protect farmland and wildlands for future generations.

Unfortunately, most members of Congress, including many influential members of the House and Senate Agricultural Committees, don’t understand the devastating toll that six decades of Farm Bill subsidized factory farming methods has taken on the land—or the power of conservation programs to reverse them.

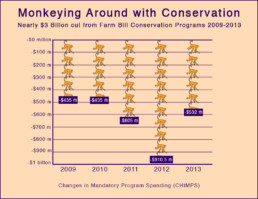

Adding insult to injury, those conservation programs that do exist rarely get the money they are promised when Farm Bills are passed. Legislators make a big deal about how the Farm Bill protects the environment. But whenever budget appropriators need savings, conservation programs are the first on the chopping block. There’s a term for this: Changes in Mandatory Program Spending, or CHIMPS.

Over the last five years, Conservation budgets have been CHIMPed by more than $3 billion, with nearly $2 billion in cuts between 2011 and 2013 alone. That’s not because there’s no demand for the programs. Three out of four applications are turned away for lack of funding.

Even common sense on-farm stewardship practices that were historically required of farm subsidy recipients are disappearing from the Farm Bill. Take taxpayer funded crop insurance. Over the past five years, subsidized crop insurance has become farmers’ preferred source of taxpayer assistance. Crop insurance policies currently come with no land conservation requirements. Because of this, they are actually causing a massive amount of previously protected land to be plowed up. Farmers anxious to cash in on record crop prices no longer have to worry about yields when taxpayer programs guarantee them against losses. Across the Great Plains, corn and soybeans are being planted on millions of acres of erodible lands that were previously deemed marginal and formerly protected through the Conservation Reserve Program. Scientists fear another Dust Bowl is in the making.

“Congress right now has the ability and responsibility to transform the Conservation Title for the next 10 years,” says Oregon Representative Earl Blumenauer. In May, Blumenauer introduced HR 1890, the “Balancing Food, Farms and Environment Act of 2013.” The bill is just one of many intended to strengthen conservation efforts into the House and Senate Farm Bills, which should come to floor votes this summer. A Coburn-Durban amendment is aimed at imposing income thresholds on crop insurance for the largest farmers. HR 1890 would provide more money for to protect land in permanent easements and reward farmers for carbon sequestration. Chellie Pingree of Maine introduced an amendment to expand supports to organic farmers.

In a political landscape hostile to environmental protection, agricultural lobbies have for decades found ways to pilfer conservation budgets to help boost crop and livestock production. Over the last ten years alone, according to the Environmental Working Group, two billion dollars in the Environmental Quality Incentives Program have been diverted to pay for the hard costs of establishing waste containment structures for concentrated animal feeding operations, laying pipe for irrigation in arid regions, and draining wetlands.

Like the Olympic Games, the renewal of the Farm Bill only comes around every four to five years. It offers the opportunity for Americans to invest in the long-term health of farmlands and the countryside. But time may be running out.

Could this year be a turning point for Farm Bill conservation reforms, like the 1985 and 1990 Farm Bills, which established far-reaching efforts to protect grasslands and wetlands across the heartland?

Clueless About Food and Agriculture?

Outside of First Lady Michelle Obama’s “Let’s Move” campaign to urge kids to exercise more and eat better, this administration remains largely indifferent to the disaster that is the country’s outdated food and agriculture policy. USDA Secretary Tom Vilsack recently argued that rural America has become politically irrelevant—a possible explanation for why the House refused to even consider a vote on a new Farm Bill last year. Maybe it’s something else. It could be that the present Congress and Administration are simply clueless about the severity of our food and farming crises.

Riding the coattails of the fiscal cliff bargain, the 2008 Farm Bill—three months past its “renew by” date—got a nine-month extension shortly after New Year’s Day. The extension could have included funds to preserve programs that help rural America and rebuild a food and farming system around the challenges of the 21stcentury. Instead, the policy—concocted in backdoor fashion without any public input—might as well have been written by lobbyists from the crop insurance, finance and agrochemical industries.

The Farm Bill extension bears little resemblance to the plan hotly debate and passed by the Senate last summer. While by no means ideal, that Senate plan would have clipped excessive commodity subsidies and reduced but still preserved important programs for conservation, organic agriculture, and rural development. This Farm Bill extension will continue sending $5 billion in direct payments to landowners whether they farm or not, whether they experience losses or not. (Both Republicans and Democrats favor eliminating such subsidies.) By extending rather than writing a new five-year Farm Bill, Congress did, however, manage to avert the dreaded “dairy cliff.” This would have reverted to a 1949 dairy subsidy program causing milk prices to spike to about $7 a gallon.

Kicking the Farm Bill down the road means we continue to invest in a backward agriculture policy. Because nothing was done to reform cotton subsidies, the US will continue to send $150 million in 2013 to Brazilian cotton farmers. This is the result of a lingering World Trade Organization ruling that declared previous US cotton supports trade distorting. Meanwhile, as Brazilian farmers benefit from the Farm Bill extension, the big losers are dozens of programs that train the next generation of US farmers and ranchers, invest in on-farm renewable energy, assist organic growers, expand farmers markets, and rebuild the infrastructure of a regionally-diversified food system.

Contrary to what many might think, the US faces a mounting list of rather alarming food and farming related challenges. Over 15 percent of the American population—mostly retired, disabled, children or underemployed—depend on food stamps, the largest budget item in the Farm Bill. Last year’s severe drought affected two-thirds of all agricultural counties, impacting crop yields, raising grain prices, and forcing livestock owners to sell off herds. Unpredictable weather patterns, we are told, are now the norm. “Superweeds” occupy 60 to 80 million acres of the country’s farmland as a result of a large-scale shift to genetically engineered, herbicide-resistant crops. Our research budgets into innovative farming strategies to address such problems are shrinking rather than expanding.

The Farm Bill exists to address problems, like these, that are not easily solved by the free market. A smarter Farm Bill would offer assistance to farmers to take care of natural resources, help for those who can’t get enough to eat, and funding for forward-thinking research to help farmers stay ahead of environmental challenges.

The good news is that the door is not yet closed on a Farm Bill. The most recent short-term extension means that a new five-year Farm Bill could be written and voted on by September. Despite “Farm Bill fatigue” setting in among many citizens who care about agriculture policy, the time to set the terms of this debate is now, as Congress struggles with the challenge of fiscal austerity and the national debt. We still have the opportunity to make the changes necessary for a healthier, more secure, and conservation-based food system. Representatives need to repeatedly hear our concerns.

Here are a few ideas that voters should be pestering the 113th Congress about:

Full funding for conservation programs to protect topsoil, clean air, fresh water and safeguard natural habitat;

Reform of the crop subsidy rules to exclude millionaires from government handouts and limit how much an individual entity can receive;

Changes to crop insurance including limits on federal funding to insurance companies and strict environmental stipulations for farming operations that enroll;

Expanded support for sustainable and organic agriculture through cost-share programs, research, and market development;

Continuation of programs that invest in a new generation of farmers and ranchers;

Initiatives aimed at increasing the accessibility and affordability of healthy nutritious foods, particularly among the young and aging.

Holding our collective breath for change won’t help. The healthy food movement needs to speak more loudly and preferably in unison on these issues. Otherwise we’ll get more of the same: food and agriculture policy that is clueless about the real problems we face in the years ahead.

Follow the Farm Bill discussions at

Sustainable Agriculture Coalition

Four Ways the Farm Bill Makes Me Crazy

The Farm Bill is a 700-page hodgepodge of laws, regulations, guidelines and payouts covering all manner of U.S. agriculture, conservation and nutrition programs. And by the end of September, Congress is supposed to re-authorize this mess, or some variant of it, for another five-plus years.

A rational, coherent blueprint for a healthy national food supply might be too much to ask. But after years of studying the Farm Bill, I'd be thrilled to see a dent made in four of its most glaring conflicts of purpose.

1. Don't subsidize what you don't want people to eat.

In broad strokes, the Farm Bill generally has three primary thrusts: 1. Nutrition spending like SNAP (formerly called food stamps), emergency food assistance, and school feeding programs; 2. Subsidies for commodity crops and income support for farmers; 3. Land, soil and ecosystem conservation. These first two are like trains on separate tracks running in completely different directions. (Come to think of it, so are the second and third. They will be addressed below.)

In early 2011, the USDA replaced its Food Pyramid with My Plate, a simple graphic representation of the food groups recommended. My Plate's message is clear: A healthy plate should be at least half full of fruits and vegetables and another 30 percent should comprise whole grains. The last 20 percent of the plate is reserved for proteins. A serving of low-fat milk or yogurt rounds off the serving recommendations.

If there were a matching USDA Subsidy Plate, however, its message would be: Fill your plate with meat and processed foods. Nearly two-thirds of the corn, over half of the soybeans, a great deal of the cottonseed and cottonseed meal, and even some of the wheat produced in the U.S. are fed to livestock. The remainder of the corn and soybeans are either processed into biofuel or industrial food ingredients. And these are the crops the Farm Bill primarily subsidizes. Fruits, vegetables and nuts--the very items the USDA wants us to eat most of--are known as "specialty crops" and currently receive only a small fraction of farm subsidies despite their high nutritional values. Well over 60 percent of commodity subsidies flow to crops fed to animals.

It's the industrial beef, hog, chicken and dairy operations that win out; subsidies mean they get cheap feed. According to the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine, the meat, egg and dairy sectors were the beneficiaries of the majority of the $246 billion in subsidies given to U.S. food producers between 1996 and 2009.

2. Don't pay polluters.

Massive dairies, hog and poultry factories and other livestock feedlots house thousands (often tens or even hundreds of thousands) of animals. Some produce as much waste as the sewage system of a small city. The difference is that animal feeding operations don't install municipal waste treatment plants to clean up their messes.

And yet this type of food production has been supported for a decade by a Farm Bill program called the Environmental Quality Incentives Program. EQIP, as it's called, must spend 60 percent of its budget on livestock producers, many of whom are the worst, environmentally speaking. And what are they spending that money on? Manure lagoons and waste trafficking.

EQIP started as a conservation program, meant to help small livestock producers keep animal waste out of creeks and waterways. But now, thanks to lobbying, the massive animal farms can be reimbursed for up to 75 percent (capped at $300,000 per owner) of their costs for animal waste storage and hauling and compliance with laws like the Clean Water Act. Should we have to pay livestock operators to comply with basic laws? Should our tax dollars build the infrastructure for massive meat, egg, and dairy factories?

Meanwhile, EQIP funds to organic farming projects are capped at $20,000 a year per operator.

3. Don't subsidize overplanting.

Nothing in the Farm Bill--nothing--continues to be more counterproductive than the complete disconnect between commodity crop subsidies and conservation programs. On the one hand, subsidies encourage farmers to plant in every inch of soil, crop insurance programs eliminate farmers' economic risks, and disaster bailouts encourage plowing even on marginal lands in areas prone to flooding and drought. On the other hand, the U.S. Department of Agriculture directs less than 7 percent of its overall spending toward conservation, much of that to right past wrongs and to clean up problems stemming from over-farming.

Consider, for example, that even as 1.7 million acres were enrolled in the Conservation Reserve Program in South Dakota between 1985 and 1995, more than 700,000 acres of grassland were converted to crops--primarily corn and soybeans (already in excess supply). This absurd process only accelerated during the last Farm Bill, as even grasslands used for hay and pasture were transformed into corn fields. Such a dichotomy makes Farm Bill conservation programs seem more like a distraction than a coordinated national stewardship strategy.

In the case of the Wetlands Reserve Program--arguably the Farm Bill's most successful conservation effort to date--only wetlands previously impacted by agricultural development are eligible for funding; you can't use the money to save pristine ecosystems (unless they're attached to land damaged by farming or ranching).

4. Don't farm corn for fuel.

The drums are finally beating against ethanol subsidies and tax breaks that suck up $7 billion per year in tax dollars. It's about time. For years Congress has mandated that gas be blended with ethanol to push our fuel supply further. And yet, we're practically spinning our wheels backwards. It takes about two-thirds of a gallon of petroleum products to sow, fertilize, irrigate, harvest and process a gallon of corn ethanol. That's minimally cutting our dependence on foreign oil.

In fact, in 2010 a full 36 percent of the U.S. corn crop was turned into ethanol. That only displaced about 8 percent of what we put in our gas tanks. Americans could save that much gas with a 1.1 mpg increase in the fuel efficiency of our cars and trucks. Here's a kicker: Ethanol-laced gas actually lowers fuel efficiency by 3 to 4 percent.

America faces numerous and complex food- and farming-related challenges in the years to come: curbing the obesity epidemic, halting the loss of habitat, stopping disease outbreaks like e. coli, bringing up the next generation of farmers and ranchers, and many more. The Farm Bill is our chance to right things that are wrong with the food system. Even small amounts of well-directed funding can do a great deal for a beginning farmer education program, habitat restoration effort, or local food project. It would help if the Farm Bill could stop fighting itself. And maybe then it can start to align along one sensible strategy: Create economically and environmentally healthy farms to grow healthy and affordable food.

Honoring The Food Animals On Your Plate

From the cream in our Monday morning coffee to the roast chicken at Sunday night dinner, we accrue an incalculable debt to food animals. We depend on them for nourishment. We gather festively around the cooking of a turkey or ham during holidays. Yet many people do not realize that most of the animals that grace our tables are the victims of harsh suffering long before slaughter.

Consider the modern turkey. It is far removed from the wild, native bird that the pilgrims roasted for those original Thanksgiving gatherings. Today’s conventional turkey, the Broad Breasted White, is an entirely industrial creature. It is bred to grow freakishly quickly and raised on grain inside massive buildings. Most male turkeys, or Toms, become so breast heavy, they can barely stand up – and certainly can’t reproduce. Artificial insemination is the only way this man-made species survives.

Such mass-production meat factories – called “concentrated animal feeding operations,” or CAFOs – exist for most of the animal food products Americans buy: cows, pigs and chickens. At least 90 percent of food animals in the U.S. are raised this way, and other countries are rapidly adopting the CAFO model as well. These enterprises are a perverse inversion of our idea of family farms with pigs rolling in the mud, cows grazing in pastures, roosters crowing from fence posts, and farmers interacting with the animals. At CAFOs, vast numbers of animals—100,000 cows on a feedlot, 30,000 chickens in a broiler shed, 1,000 hogs in a windowless warehouse—are confined in pens or cages, often kept alive with regular doses of antibiotics.

As CAFOs take over the food system, it is clear that there is already plenty of animal protein in our diets. Americans now eat an average of 33 pounds of cheese each year, for example, largely because of the flood of cheap milk coming from dairy CAFOs. This is three times the per capita consumption of the 1970s. Cheese is the largest source of saturated fats in our diets, which tend to raise cholesterol levels and are linked to heart disease. Dairy products, meat, poultry, and eggs don’t have to be nearly so cheap or abundant – and yet we are raising 10 billion food animals in the United States every year.

The high costs of factory-farmed foods are being paid for by the animals, rural communities, taxpayers, and the environment. Large-scale animal operations generate the sewage output comparable to a small metropolis.The waste oozing from these highly concentrated production systems fouls the air, land, and water. Sadly, if you purchase animal products from fast food restaurants, supermarkets, big box stores, or other mainstream outlets, there is a strong chance that you are eating at the expense of someone else’s community well-being.

You don’t have to become a vegan or vegetarian to opt out of this system that might best be described as “organized irresponsibility.” (Those are certainly viable options, however.) Some of the country’s best small farmers are demonstrating that traditional methods of livestock production are practical and economically viable. They are raising locally adapted breeds of livestock on pastures where the animals eat a more natural diet, grow more slowly, and naturally socialize. These animals are also raised without routine doses of antibiotics and growth hormones, essential tools in industrial CAFO production. Third-party certification organizations such as Animal Welfare Approved have established standards combined with regular audits to encourage such humane production practices.

Still, labels can be confusing, and some like “natural” and “healthy” are misleading. The best way to know where your food comes from and how it was produced is to know your farmer.

The other way to reduce the role of CAFOs is to scale back the amount of meat we consume. Many individuals are simply orienting their meals around more grains and vegetables with smaller portions of higher quality, sustainably sourced meats, dairy, and eggs. Another groundswell is the Meatless Monday campaign, which has already been embraced by chefs, restaurants, food services, k-12 schools, and college campuses.

Attending to the conditions under which your food is raised is a profound way of giving thanks to the animals that nourish you daily. It can also lead to some of the most satisfying meals you’ve ever shared or tasted.

Resources:

CAFO: The Tragedy of Industrial Animal Factories

Grass Pastured Meats

This piece was originally published on Huffington Post.

Confessions of a Reluctant Wonk

First, a confession. I am a reluctant wonk. Despite writing rather extensively about food and agriculture policy, acronyms are not what motivate me in the morning. After about a half an hour of studying something as dense as the Farm Bill, I need a diversion, a few minutes of deep breathing outside with my feet on the ground, or some quality time with Fanny, my Australian shepherd.

I do believe that agriculture is indeed a public good. Food and farm policy are not a necessary evil but a real privilege and opportunity for a country and its people. It is wise to invest in conservation, clean water, soil protection, and habitat enhancement for our collective good. The natural world, well attended, cannot keep pace with the growth demands of the industrial economy and Wall Street. Unfortunately, our rural lands, farm animals, and agriculture workers are being driven by efficiency, industrial concentration, and profit taking. Rather than investing in tangible returns and long-term security, agriculture policy is pushing us toward the brink of collapse on many fronts.

For those who care about healthy food, the Farm Bill is something we all need to digest—even in small helpings. The information is out there, accessible and more organized than ever before, even if the situation is not so rosy. (Check out www.farmpolicy.com everyday for a week to get started.)

The Farm Bill is a massive legislation that is revisited every five to seven years. The next renewal is scheduled for 2012 but it could likely drag on into 2013 or beyond. For the last few decades the Farm Bill has been dominated by two primary political forces: a nutrition and hunger bloc that fights for food stamps (now known as SNAP) and other assistance; and the commodity agriculture lobby (corn, cotton, wheat, rice, soybeans, dairy, sugar producers, and concentrated animal feeding operations or CAFOs). This is your basic quid pro quo. Urban legislators get food assistance for the 40 million Americans facing hunger on a regular basis. Farm country legislators bring home the bacon to huge agribusinesses that are now raking in record profits.

My least favorite of these commodity players hijacking taxpayer dollars are the CAFOs. Not only are their factory animal farms morally reprehensible, they are fouling the air, water and land in the communities where they have taken over and are feasting at the public trough in the process. Their economic model is based upon a steady supply of Farm Bill subsidized feeds—corn and soybeans—that has saved them billions of dollars over the last decade. (This is well documented in a report by Timothy Wise and Elanor Starmer from Tufts University). In 2002, the CAFO industry began raiding precious Farm Bill conservation dollars to pay for nasty manure lagoons and waste management infrastructure. A single CAFO investor can qualify for $450,000 in Environmental Quality Incentive Program dollars to pay for his or her own pollution compliance. (Read Martha Noble’s essay inThe CAFO Reader for a more detailed summary.)

One would think that once the CAFOs and other commodity producers get their 10 billion to 20 billion dollars each year from the taxpayers, their lobbyists would be content to let the rest of the players fight over the scraps: a few billion here for conservation, a few million here for rebuilding local food capacity, a few million for those organic farmers who pay high certification costs just to prove they are doing the right thing. But agribusiness is not content. They are fighting for every last cent of Farm Bill dollars and doing all they can to paint the burgeoning good food movement as fringe and meaningless.

Last year, Senators Mc Cain (R-AZ), Chambliss (R-GA) and Roberts (R-KS) publicly attacked Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack and a small program named Know Your Farmer, Know Your Food. KYF 2 (in Wonk speak) was spending approximately $65 million to rebuild local food systems around the country, including developing new markets in urban areas for rural farmers hoping to expand their businesses. In highly divisive language, the Senators claimed that this money was benefitting organic hobby farmers supplying urban elites at farmers markets, rather than “Production Agriculture.” This is the term for heavily subsidized monoculture commodity farmers that largely grow crops we don’t directly eat. Just to give some perspective on that $65 million Know Your Farmer program budget, Brazilian cotton farmers received $165 million last year from our government in retaliation for past U.S. cotton subsidies deemed illegal by the World Trade Organization. The Senators wrote no nasty letters to the Secretary about those payouts to farmers in another country as far as I know. Then again, there are a lot of cotton farmers in Arizona and Georgia.

Last week the rules were finalized on another 2008 Farm Bill program called the Farm and Ranchland Protection Program (FRPP). One would hope this money would go to protect beautiful farmlands in areas threatened by sprawl and development. But in keeping with their strategy of fighting for every last cent of the Farm Bill pie, agribusiness lobbyists were able to make a CAFO manure lagoon (a cesspool of waste) eligible for protection under Farm and Ranchland Protection Program easements. Maybe there is something I don’t quite understand — such as even small operations have such holding facilities — but somehow this doesn’t seem what the program was intended to preserve. (Read the National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition’s report here.)

As you can see, foodies, foodists, healthy food activists, and concerned citizens have no choice but to begin to understand the detailed maze of farm policy. Our challenge is to move from acting individually to developing collective clout. It’s the only way voting with our forks might begin to change the enormous power corporate agribusiness wields over our food system.

Food Safety Bill Ignores CAFOs; Spurns Small Farmers

[Posted by Emmett Hopkins, Watershed Media research assistant and Foggy River Farm farmer.]

In a rush to pass some sort—any sort—of food safety bill, Congress has penned a piece of legislation that might actually harm the very farmers that hold the answers to our food safety challenges.

Before leaving on its August recess, Congress passed House Resolution 2749 (HR 2749). This bill gives the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) sweeping powers to regulate American food producers, but in doing so, it does little to distinguish between huge multinational corporations and small family farms producing food to sell in their local communities. According to Opencongress.org, HR 2749 grants the FDA “the authority to regulate how crops are raised and harvested, to quarantine a geographic area, to make warrantless searches of business records, and to establish a national food tracing system.” To fund this effort, the bill proposes raising a $500 registration fee on any facility “holding, processing, or manufacturing” food.

As we wait for the Senate to return from recess and take up this bill, it is worth considering its effects on small-scale farmers and local food producers. Across America, communities are working to create strong, viable regional food systems. From Alabama to Washington, locals are supporting small sustainable farms, establishing farmers markets, creating local food co-ops. They do this not just because they appreciate the sweet perfection of just-picked tomatoes and melons—but also because they know that by strengthening local farms and food processors they are more likely to have a reliable supply of safe, healthy foods for their children and their grandchildren. Who needs a bureaucratic food registry system when you can drive across town and visit the farmers who grew your lettuce, made your cheese, or canned your pickles?

In its current form HR 2749 could have a disabling effect on many small scale farmers. The $500 registration fee required to be paid by any farm that processes food is unreasonable to ask of small farms. During acommittee hearing, one of the bill’s sponsors Henry Waxman (D-California) pointed to large corporate food producers in his defense of the fee structure: “In the recent peanut (salmonella) outbreak, Kellogg’s alone lost $70 million. Faced with such a dire situation, I think it is reasonable to ask the food industry to chip in.” This is all well and good, but the problem arises when Waxman and his colleagues fail to differentiate between Kellog’s—which reported $12.8 billion sales in 2008—and little Grandma’s Jams and Jellies that made, let’s say, $12,800 in 2008.

Several farm organizations and US Representatives have expressed their concern about the fee structure:

Representative Sam Farr (D-California), during a committee hearing, said this:

"I have deep concerns ... about the fee structure in the measure, which would charge a farm family making jams or syrup or cheese the same fee as a processing plant owned by a multinational corporation employing hundreds or thousands or workers. This strikes me as not only unfair but contrary to federal farm policy that has encouraged small and mid-sized family farms to get into small scale value-added enterprises to survive economically. I am seeking an assurance ... that a more progressive fee structure will be found that does not inhibit our farm families from taking advantage of new markets."

A letter presented to Henry Waxman by seven concerned members of Congress stated:

The National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition and the National Organic Coalition, in a letter to bill sponsor Representative Dingell (D-Michigan), wrote this:

"While H.R. 2749 bill exempts facilities that sell over 50.1% of their processed products directly to the consumer, it still imposes a fee on those who primarily sell wholesale. We represent a large number of farmers who sell their value-added products to the wholesale market as well as a large number who sell direct to consumer, and in fact, most farmers increasingly do some of each. […] H.R. 2749 requires facilities of all size, regardless of whether their annual revenue stream is $1,000 or $1 million or $100 million, to pay the same fee. […] This is a fundamental issue of equity. The tax in the bill as written and approved by the House violates the basic principle of ability to pay which is the bedrock of our system."

While the proposed law includes certain exemptions for farmers that primarily sell directly to consumers, restaurants, and grocery stores, farms that sell primarily to other local venues such as caterers and school or hospital cafeterias would not qualify. The NSAC and NOCworry that “there is increased demand for locally-produced agricultural products in school cafeterias, but as it stands, the language in HR 2749 would not exempt farmers selling direct to institutional settings which could dampen farmer interest in these important new markets that stand to provide healthy, fresh food to our nation’s children.”

Let’s stop and think for a minute about where the most prevalent food safety problems come from. Salmonella and E. coli are the bacteria that seem to most often cause outbreaks in the US—and both originate exclusively from animals. E. coli lives in the gut of ruminants; The main culprit for spreading this disease is cattle. The corn-fed cattle in industrial feedlots carry by far the most E. coli bacteria. (A 2009 studyby the USDA found that “When cattle were abruptly switched from a high grain diet to an all hay diet, total E. coli populations declined 1,000-fold within 5 days.”)

Miraculously, however, it seems that all of the large-scale industrial animal operations would be exempt from the regulations proposed under this bill (see "USDA Exemptions" section of bill ongovtrack.us)....when in fact it is these industries where most of our food-borne illnesses begin. It is the massive industrial farms that need targeting—not a misguided effort to control the demonized "leafy greens." Let's focus our attention where it is truly productive: the mega meat feedlots and slaughterhouses. Instead of HR 2749, Congress would be better suited to pass something closer to Kevin's law—a.k.a. the "Meat and Poultry Pathogen Reduction and Enforcement Act." This bill was introduced by Anna Eshoo (D-California) along with 36 Republican and Democratic co-sponsors in 2005, but never became law. It would have focused the fight for food safety squarely on the large meat producers, where it belongs.

The idea of promoting food safety is a noble one: To protect consumers from food-borne illness that could suddenly and silently harm them or their families. The solution proposed by HR 2749, however, fails to focus narrowly on the most likely sources of illness: meats and other foods processed in massive facilities, and food imported from abroad. Instead, it risks slowing down the regional food movements that actually promise solutions to our food safety problems. Rather than holding back small-scale farmers, we need to be urging them forward. They represent the future of American food: a network of regional food systems where food is traceable and farmers are accountable because they are right down the road.

*Visit the Community Alliance with Family Farmers (CAFF) website for links to various Congressional hearings, statements by farm organizations, and information about other shortcomings of HR 2749.

*Visit Wild Farm Alliance’s compilation of articles related to the food safety bill and other related topics issues.

*Read Carolyn Lochhead’s San Francisco Chronicle article on resistance to the bill.