The Land of Stinkin’: When a Mega Dairy Takes Over

Imagine a series of pits that, if combined, would cover an area 40 acres in size carved 20 feet deep. Laid out as a perfect square, each side is 1,320 feet long, enough to hold 16 football fields. Now imagine it full of millions of gallons of festering manure from over 5,000 dairy cows plunked down into rural Jo Daviess County in northern Illinois. Imagine also, that these cesspools would be excavated from a porous Karst geological formation, with the propensity to percolate directly into the groundwater, along with a cocktail of nitrates,phosphorous, hydrogen sulfide, bacteria, and other substances like antibiotic drugs.

If your state’s Environmental Protection Agency doesn’t bother fulfilling its obligations to permit such potential pollution hazards under the Clean Water Act, you have little choice but to start your own citizen activist organization. For three years, the HOMES group (Helping Others Maintain Environmental Standards) has been emptying their pockets for attorneys fees, organizing rallies, documenting abuses, and constructing a legal case against a California mega-dairy that wants to—as they see it—invade their community, an agricultural region with many legacy farms spanning multiple generations.

The challenge before the HOMES group is made all the more difficult because Illinois communities have lost the ability to refuse such a siting of an industrial animal factory operation in their area for concerns of protecting their own public health. “Local control” over such decisions, in Illinois as in many other states, has been relegated to the state level. In fact, just this week a HOMES' group appeal was denied by the Illinois Supreme Court, affirming that the state's Department of Agriculture has the ultimate say in CAFO siting decisions, and stripping citizens' rights to sue for improper implementation or enforcement of regulations.

I participated in a community discussion about CAFOs sponsored by the HOMES group last week. It was an opportunity to listen to talks from long-time activists Dr. Kendall Thu of Northern Illinois University (contributor of a great essay to my CAFO book) and Dr. John Ikerd, retired agricultural economist at the University of Missouri, whose work greatly informed the book’s pieces on the community impacts of industrial animal factory agriculture. I also had a good chance to meet other committed anti-CAFO activists, such as grain farmer Karen Hudson and public interest attorney Danielle Diamond, both with theSocially Responsible Agriculture Project.

This leg of the CAFO outreach campaign started about an hour west of Chicago, driving west and south through the Land of Lincoln, known by the anti-CAFO activists as the Land of Stinkin’. There are over 3,200 CAFOs in the state, primarily hog and dairy operations. To pump a steady stream of feed into these protein factories, Illinois produces a staggering amount of corn. We drove for hours and hours at the 65 mph speed limit, passing field after monoculture field of corn, fields right up to the highway, right up to farm houses, right next to mutated suburban developments with barely a forest or hedgerow or clump of trees in sight. As they say, planted “fencerow to fencerow.” In this day of soaring commodity prices, soaring demand for animal feed and ethanol, it seems the only way an Illinois farmer would maintain any habitat at all is if the government (aka taxpayers) pay them for it.

The mega-dairy that the HOMES citizen activist group is fighting against is owned by A. J. Bos, a corporate agribusiness from California. It has already established one of the country’s largest dairies in northeastern Oregon, Threemile Canyon, which I have visited and am told is now the third largest emitter of airborne ammonia in the nation—no small achievement if true. One of the departing acts of public service of the Bush administration was to remove Environmental Protection Agency restrictions on reporting of air emissions including ammonia, an airborne pollutant and health hazard that can literally travel for miles from a livestock operation. The CAFO industry has been given a get out of jail free card when it comes to Clean Air Act violations.

This large-scale industrial assault is set against the backdrop of the unraveling meltdown of the Fukishima Daiichi nuclear power plant in Japan and I can’t help thinking of the out of control scale of our industrial operations. The CAFO industry is essentially telling us they’re too big to fail, we need their massive confinement systems if we want a cheap and abundant food supply. The costs of polluting a community’s groundwater, eroding their living standards, degrading their air quality and filling the countryside with the odors of thousands of cows producing more manure than milk on a daily basis and never touching a blade of grass are simply the price of cheap dairy products. What they don’t say is that the jobs a CAFO actually brings in to an area will most likely be very few and low paying. It will also spell the end for numerous small and mid-size independent producers in the region. And in time, once a community is opened up to the animal factory industry, it begins a downward economic spiral with few other development options.

As the HOMES group fights with every breath to prevent becoming an ecological sacrifice zone, it appears that the owners of California-based A. J. Bos have no intentions of living anywhere near the operation. State and federal regulators have made the expansion of such filthy businesses possible. It is humbling to witness such a tragic abandonment of civic defense.

Glimmers of hope remain. Although construction of the mega-dairy is well underway, the barns remain incomplete and no animals are confined yet. Last October, a bright purple leachate of rotting silage, applied onto fields of the A. J. Bos land, contaminated a tributary to the Apple River. As a result, the US EPA is now questioning whether this CAFO can possibly be a “zero discharge facility” as the corporation has alleged. (That's essentially the way the system works. A CAFO promises they are not going to discharge, and the government believes them.) Meanwhile, a second citizens’ activist group, Illinois Citizens for Clean Air and Water, is successfully petitioning the US EPA to withdraw the Illinois EPA’s Clean Water Act permitting authority because of their failure to properly regulate existing CAFOs. The pressure is now on the Illinois EPA to step up their regulatory oversight or risk US EPA taking over administration of the Clean Water Act in the state.

In northern Illinois, and across the country, everyday citizens are doing the work of the state and federal government to prevent a complete fouling of their communities by industrial animal factories. This is hardly the time to dismantle the Environmental Protection Agency, a pursuit senators and representatives from both sides of the aisle are currently attempting. In many states, the Clean Water Act remains one of the only tools that offers citizens any kind of legal recourse and environmental protection from installations such as shit spewing absentee landowner corporate mega-dairies. In an age of increasing voluntary corporate compliance, community self-preservation hangs by barely a thread.

Bag the "Ag Gag" Bills

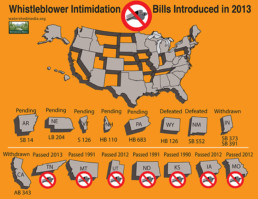

When might it be punishable to report a criminal activity? When it takes place inside a poultry warehouse, slaughterhouse, or on a cattle feedlot. That’s the upshot of a new wave of so-called “ag-gag” bills passed in state legislatures around the nation, the latest of which, AB 343, was introduced in California last month.

When might it be punishable to report a criminal activity? When it takes place inside a poultry warehouse, slaughterhouse, or on a cattle feedlot. That’s the upshot of a new wave of so-called “ag-gag” bills passed in state legislatures around the nation, the latest of which, AB 343, was introduced in California last month.

“Ag gag” laws have been put forth by the meat industry to criminalize the reporting of animal cruelty by anyone—journalists, activists, or whistleblowers. They are intended to prohibit the release of videotapes or photographs that document what happens inside factory farms and meat processing facilities, often with the threat of jail time. The real goal of these laws is to “chill” a person’s resolve to make public any illegal behavior such as beating or torturing captive animals, often using the police to seize their materials.

Whistle blower intimidation laws incite the ultimate cynicism about politics. For instance, the California bill is titled, “Duty to Report Animal Cruelty,” when in fact, its true aim is to squelch dissemination about the brutality of factory farming. If passed, AB 343 would require would-be whistle blowers to submit any visual evidence to law enforcement within 48 hours of taking a photograph or video or be subject up to a $500 fine. It also encourages the submission of any proof to the owner of the animals.

This would effectively force reporters to forfeit their anonymity. A worker might face retaliation from an employer. A journalist might not have time to adequately pursue a lead. Offending operators would be alerted that they are under suspicion. Meanwhile, industry maintains the appearance that it cares about animal welfare.

Big agricultural lobbies are desperate to avoid the kind of public relations disaster that befell the Hallmark Meat Packing Company. In 2008, secret cameras showed downer dairy cows being chained, dragged, and electrically prodded to slaughter at Hallmark’s facility in Chino, California. Such illegal practices were exposed by a disillusioned plant worker and the Humane Society of the United States. The USDA’s Commodity Procurement Branch, which distributes beef to the National School Lunch Program, was one of Hallmark’s biggest customers. The ensuing news coverage resulted in the largest recall of meat products in history and the ultimate closure of the plant.

Kansas, Montana, and North Dakota already have laws making it punishable to photograph an agricultural operation without consent of the owner. Utah, Missouri, and Iowa passed ag gag laws last year. In Iowa, where recent undercover videos have shown blatant animal abuse at egg and hog facilities, a first offense can land you in jail for up to a year. A second offense is considered an aggravated misdemeanor with up to two years jail time.

What’s happening in California is part of a nationwide effort. Already this year, whistleblower suppression laws similar to California’s have been filed in Arkansas, Indiana, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New Mexico, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Vermont, and Wyoming.

The timing of this legislative push is extremely troubling. The federal government’s budget sequestration could significantly reduce funding for USDA meat inspectors. The system is already challenged to keep up with continual changes in production lines that process animals at ever-increasing speeds. That means even as the government has less resources for oversight, industry is working to suppress whistle blowing.

Why is the meat industry on the defensive? Even perfectly legal practices are often distasteful to the public. In the face of rising public awareness about genetically modified crops, contaminated eggs, downer animals, etc., the meat industry has been jolted into anti-democratic tactics to muzzle its critics.

Newly elected California Assemblyman, Jim Patterson (23rd District), introduced AB 343 to the state legislature with the backing of the California Cattlemen’s Beef Association. While it might appease the powerful California meat lobby, this law would go against the will of California’s majority. Most citizens want animals to be raised more humanely. California’s Proposition 2, the Prevention of Farm Animal Cruelty Act, passed with 63 percent of the vote. Restrictions on animal cages are slated to go into effect January 1, 2015.

When government fails to fulfill its regulatory oversight, citizens—including the news media—often have no choice but to become their own watchdogs. There is a noble American tradition of journalism related to food production concerns. At the turn of the 20th century, Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle described appalling conditions in Chicago’s slaughterhouse district. Its publication greatly influenced new laws to regulate food safety and meat processing. Now is the time to turn the tide against a national assault on greater transparency and meaningful reform in the food system.

The Farm Bill is Really A Food Bill

America’s first Food Stamps were orange or blue. Citizens eligible for government relief bought a one dollar orange ticket at face value, redeemable for any food item. Accompanying every orange stamp was a free blue ticket worth 50 cents, that could be used to buy surplus food items: meat, milk, eggs, or seasonal produce that the government purchased from farmers. This was the 1930s, and federal nutrition assistance, along with support to help farmers conserve the soil and earn fair prices, were essential elements of what we know today as the Farm Bill. Food stamps were what helped many desperate families put food on the table.

Eighty years on, Food Stamps continue to be one of the ways America grapples with its hunger problems. Paper coupons have given way to less stigmatized Electronic Benefits Transfer (EBT) cards—monthly monetary allotments assigned to a debit card. But the numbers are staggering. As a result of the economic contraction that started in late 2007, nearly 50 million people, one-third of them children, are now in poverty (up from 31 million in 2000). The number of U.S. citizens applying for food stamps, now known as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), has nearly tripled since 2001. In the month of October 2012 alone, three years into our economic “recovery,” nearly 1 in 7 Americans—47.5 million people— participated in the SNAP program.

These monthly Food Stamp enrollment tallies, however, don’t demonstrate the magnitude of poverty in the U.S. or the true function of the program. Critics of big government and social assistance often use the Food Stamp program as a punching bag for wasteful, excessive and fraudulent entitlements. But the fact is, a majority of people use Food Stamps as a temporary safety net between jobs—not as a permanent solution to hunger. Many are working families struggling to raise themselves out of poverty. USDA estimates that as many as 65 million Americans received SNAP benefits for at least one month during 2012—1 in 5 Americans.

“People don’t aspire to enroll in the SNAP Program,” says Stacey Dean, of the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities. “By far, the SNAP Program serves people who, because of the stress and hardship of poverty, face a genuine lack of access to healthy and affordable foods.”

Even in the era of 99-cent value meals, Food Stamps play a crucial role in providing calories to hungry Americans. As the economic recovery drags on, and as deficit reduction talks heat up, the annual Food Stamp budget—which now totals $75 billion per year—will become a prime target for cost cutters. The values of food assistance must be part of those deliberations.

- Food stamps are part of the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Farm Bill. While most people associate the Farm Bill with subsidies for corn and soybean farmers, in fact, its largest line item is the SNAP program, which accounted for more than 75 cents of every dollar spent by the Department of Agriculture in 2012.

- The Food Stamp program mainly serves people in need. The USDA’s official term for hunger is “food insecurity.” These are people who regularly skip meals because of a lack of resources. It could be a senior citizen, with hefty medical bills and fixed income, who must choose between medicine and food. Or it could be one out of every six American children for whom Food Stamps along with the School Lunch, Breakfast and Snack programs governed by the Child Nutrition Act, are an essential bridge between hunger and starvation.

- Many food stamp recipients have employment income. Over 60 percent of participating households earn income that they contribute toward the family food budget—it’s just not enough to stave off hunger.

4 . No one is buying filet mignon with food stamps. The maximum monthly allotment—$200 per individual and $668 for a family of four—nets out to around $2 per meal. Big city mayors, celebrity chefs such as Mario Batali, and others have taken on the challenge of living on a Thrifty Food plan for a week at a time. All have complained about temporarily foregoing caffeine, snacks, and things many Americans take for granted—and feared running out of money.

- Food stamps function as an economic stimulus. President Obama’s economic stimulus plan (the American Recovery Reinvestment Act of 2009) provided tens of billions of additional dollars for food assistance programs. Studies show that every Food Stamp dollar spent actually generates at least $1.74 in the broader economy. This is called a “multiplier effect.”

USDA Secretary Tom Vilsack regularly reminds audiences that the Food Stamp program helps farmers too. “Producers get somewhere between 15 and 16 cents of every food dollar that’s spent in a grocery store and a restaurant,” he told the American Farm Bureau Federation in Nashville in January 2013. “And to the extent that families are empowered during struggling times to be able to buy adequate groceries for their family, at the end of the day that also helps American producers.”

- Food stamps have a positive effect on health and nutrition. According to the Food Research and Action Center, the SNAP Program lifted nearly 4 million Americans above the poverty level in 2011 by boosting monthly income. Providing relief from hunger yields positive impacts on body weight, learning abilities, and reducing the incidence of chronic diseases—particularly among children.

The recent rise in Food Stamp enrollment offers an important window into the crisis of poverty and hunger in America. Some might view it as solid proof of failed economic policy. Instead we should look at as a way to assess whether and how government is doing its duty—investing in the health and well-being of all of society for the long term.

Clueless About Food and Agriculture?

Outside of First Lady Michelle Obama’s “Let’s Move” campaign to urge kids to exercise more and eat better, this administration remains largely indifferent to the disaster that is the country’s outdated food and agriculture policy. USDA Secretary Tom Vilsack recently argued that rural America has become politically irrelevant—a possible explanation for why the House refused to even consider a vote on a new Farm Bill last year. Maybe it’s something else. It could be that the present Congress and Administration are simply clueless about the severity of our food and farming crises.

Riding the coattails of the fiscal cliff bargain, the 2008 Farm Bill—three months past its “renew by” date—got a nine-month extension shortly after New Year’s Day. The extension could have included funds to preserve programs that help rural America and rebuild a food and farming system around the challenges of the 21stcentury. Instead, the policy—concocted in backdoor fashion without any public input—might as well have been written by lobbyists from the crop insurance, finance and agrochemical industries.

The Farm Bill extension bears little resemblance to the plan hotly debate and passed by the Senate last summer. While by no means ideal, that Senate plan would have clipped excessive commodity subsidies and reduced but still preserved important programs for conservation, organic agriculture, and rural development. This Farm Bill extension will continue sending $5 billion in direct payments to landowners whether they farm or not, whether they experience losses or not. (Both Republicans and Democrats favor eliminating such subsidies.) By extending rather than writing a new five-year Farm Bill, Congress did, however, manage to avert the dreaded “dairy cliff.” This would have reverted to a 1949 dairy subsidy program causing milk prices to spike to about $7 a gallon.

Kicking the Farm Bill down the road means we continue to invest in a backward agriculture policy. Because nothing was done to reform cotton subsidies, the US will continue to send $150 million in 2013 to Brazilian cotton farmers. This is the result of a lingering World Trade Organization ruling that declared previous US cotton supports trade distorting. Meanwhile, as Brazilian farmers benefit from the Farm Bill extension, the big losers are dozens of programs that train the next generation of US farmers and ranchers, invest in on-farm renewable energy, assist organic growers, expand farmers markets, and rebuild the infrastructure of a regionally-diversified food system.

Contrary to what many might think, the US faces a mounting list of rather alarming food and farming related challenges. Over 15 percent of the American population—mostly retired, disabled, children or underemployed—depend on food stamps, the largest budget item in the Farm Bill. Last year’s severe drought affected two-thirds of all agricultural counties, impacting crop yields, raising grain prices, and forcing livestock owners to sell off herds. Unpredictable weather patterns, we are told, are now the norm. “Superweeds” occupy 60 to 80 million acres of the country’s farmland as a result of a large-scale shift to genetically engineered, herbicide-resistant crops. Our research budgets into innovative farming strategies to address such problems are shrinking rather than expanding.

The Farm Bill exists to address problems, like these, that are not easily solved by the free market. A smarter Farm Bill would offer assistance to farmers to take care of natural resources, help for those who can’t get enough to eat, and funding for forward-thinking research to help farmers stay ahead of environmental challenges.

The good news is that the door is not yet closed on a Farm Bill. The most recent short-term extension means that a new five-year Farm Bill could be written and voted on by September. Despite “Farm Bill fatigue” setting in among many citizens who care about agriculture policy, the time to set the terms of this debate is now, as Congress struggles with the challenge of fiscal austerity and the national debt. We still have the opportunity to make the changes necessary for a healthier, more secure, and conservation-based food system. Representatives need to repeatedly hear our concerns.

Here are a few ideas that voters should be pestering the 113th Congress about:

Full funding for conservation programs to protect topsoil, clean air, fresh water and safeguard natural habitat;

Reform of the crop subsidy rules to exclude millionaires from government handouts and limit how much an individual entity can receive;

Changes to crop insurance including limits on federal funding to insurance companies and strict environmental stipulations for farming operations that enroll;

Expanded support for sustainable and organic agriculture through cost-share programs, research, and market development;

Continuation of programs that invest in a new generation of farmers and ranchers;

Initiatives aimed at increasing the accessibility and affordability of healthy nutritious foods, particularly among the young and aging.

Holding our collective breath for change won’t help. The healthy food movement needs to speak more loudly and preferably in unison on these issues. Otherwise we’ll get more of the same: food and agriculture policy that is clueless about the real problems we face in the years ahead.

Follow the Farm Bill discussions at

Sustainable Agriculture Coalition

PINK SLIME by Becky Weed

I am a farmer/I am a citizen, and this is what ‘we’ are being told:

We must raise or at least finish our animals in cages and feedlots because it is ‘more efficient’.

Even our animals that start on pasture must end in feedlots, because they ‘finish more quickly’.

We must feed heavy grain diets to ruminants evolved to live on grass, inducing low-grade illness and the practice of feeding subtherapeutic antibiotics --- because that ‘enhances growth rates’.

We cannot quit subtherapeutic feeding of antibiotics because it would be too expensive.

We must implant growth hormones to make our animals grow faster because that is most ‘profitable’.

We can extend the output of such feedlots by scavenging the meaty bits admixed with pathogen-prone fatty exteriors, and disinfecting the resultant ‘pink slime’ with ammonia gas. We must serve this augmented ‘hamburger’ to our populace, unlabeled, because it ‘adds value’.

We must spray chemicals on our fruits, vegetable, grains, and into our soils, because it is ‘cleaner’.

We must work, or hire others to work, in conditions that affluent Americans shun for themselves or their children.

We must burn up the carbon in our once-organic-rich soils in order to maximize production with ‘modern’ farming. We must displace food production with ethanol production because it ‘conserves’ carbon-based fuels.

We must purchase crop insurance via government programs rather than building our own crop insurance by building our soils and our crop diversity.

We must grow crops with diminished nutrients because modern, high-yielding Wonder Bread varieties are ‘best’.

We must feed the food derived from such management to our children.

We must plant only a few crops for fuel and livestock feed on such a vast portion of our continent that we disrupt the natural migrations of birds, mammals, pollinators, and water, because it is more ‘efficient’.

We must kill even our most iconic and remnant species, such as buffalo, because their vestigial grasslands interfere with our ‘system’.

We must degrade our waterways, air and soil with the effluent of modern agriculture, because it is most ‘efficient’.

We must purchase and plant the output of centralized biotechnology companies, because that is more ‘efficient’ than following a farmer’s curiosity, drive and wherewithal to breed seed suited to our local landscapes and cultures.

We should be grateful for the plentiful food thus produced, even if we observe increasing obesity diabetes, and malnutrition even among the ‘well-fed’.

We must be grateful for this ‘cheap’ food.

We must endorse these mandates of modern agriculture, while asserting that we are salt of the earth, and that we deserve to maintain our ‘way of life’ even as our food system degrades everyone else’s

If we choose to reject these mandates of ‘modern’ agriculture and farm differently, eat differently, vote differently, then we are quaint, callous, elitist and irrelevant.

We must feed the world, now seven billion, soon nine, then twelve, then what?

I am a farmer/ I am a citizen, and ‘we’ are telling us:

We are indeed grateful for the abundance, ingenuity and hard work that has brought us all much good food and good fortune, and it is time we take stock. How many compromises equal ‘modern’?

It is not our job to fill the Petri dish to bursting point.

The earth is our matrix and regulator. Neither trade associations, nor insurance companies, nor governments, nor universities, nor corporations, nor stock markets, nor our neighbors will superceed its natural systems’ ultimate grasp.

Perhaps some of us are too different to fit the rhythm of modern agriculture---too small, too poor, too new, too foreign, too female, too contrary, too dry, too wet, too close to the land?

Perhaps it is our job to lead the colony to pause, to feed our hearts and our brains, not just our bellies and our banks.

Efficient? Cheap? Robust? Equitable? Durable?

Farmers, of all people, could be the most qualified to recognize and explain that the current practices and trajectories take us to a place we cannot afford, and that we can scarcely want. That is, if we would speak our minds.

Pink slime is only the most recent manifestation, at the output end, of a more deep-seated, long-brewing slurry at the heart of American agriculture. This critique of the half-century-old corn-soybean-feedlot-dominated regime of American agriculture is not an attack on farmers, but is rather a plea to farmers, to awaken to our own complicity in, and our own power to change, the very system that we have allowed to compromise our values, our status, our land, and our futures. Pervasive propaganda notwithstanding, it does not have to be this way, because it cannot continue to be this way.

Have we entered Alice’s rabbit hole, where governors defend pink-slime manufacture for its job creation, even as the numbers of farmers, ranchers and cows continue to dwindle; where Farm Bureau policies perpetuate the dominance of a continental corn desert, even as their roadside posters invoke bucolic red barns and ranchers with calves-in-their-arms; where Monsanto patents life forms and prosecutes farmers, even as it bankrolls a $30 million dollar PR campaign to resurrect agriculture’s sullied reputation?

We have watched and sometimes profited in recent decades as the complex maze of subsidies, lobbies, markets, revolving doors and ignorance have rendered our legislative, executive and judicial branches impotent to find a path out. Consumers are trying to peer down the rabbit hole; scientists are tweaking the dials and reporting some news, but farmers, especially farmers, can and must blast open the portals and reclaim.

Becky Weed is co-owner of Thirteen Mile Farm in southwest Montana. Thirteen Mile runs a small wool mill and is currently revising its long-term sheep operation, collaborating with a young farmer to add vegetables to its lamb and wool marketing. Weed has worked on her own place and with others to raise livestock while coexisting with native carnivores. www.lambandwool.com/

Four Ways the Farm Bill Makes Me Crazy

The Farm Bill is a 700-page hodgepodge of laws, regulations, guidelines and payouts covering all manner of U.S. agriculture, conservation and nutrition programs. And by the end of September, Congress is supposed to re-authorize this mess, or some variant of it, for another five-plus years.

A rational, coherent blueprint for a healthy national food supply might be too much to ask. But after years of studying the Farm Bill, I'd be thrilled to see a dent made in four of its most glaring conflicts of purpose.

1. Don't subsidize what you don't want people to eat.

In broad strokes, the Farm Bill generally has three primary thrusts: 1. Nutrition spending like SNAP (formerly called food stamps), emergency food assistance, and school feeding programs; 2. Subsidies for commodity crops and income support for farmers; 3. Land, soil and ecosystem conservation. These first two are like trains on separate tracks running in completely different directions. (Come to think of it, so are the second and third. They will be addressed below.)

In early 2011, the USDA replaced its Food Pyramid with My Plate, a simple graphic representation of the food groups recommended. My Plate's message is clear: A healthy plate should be at least half full of fruits and vegetables and another 30 percent should comprise whole grains. The last 20 percent of the plate is reserved for proteins. A serving of low-fat milk or yogurt rounds off the serving recommendations.

If there were a matching USDA Subsidy Plate, however, its message would be: Fill your plate with meat and processed foods. Nearly two-thirds of the corn, over half of the soybeans, a great deal of the cottonseed and cottonseed meal, and even some of the wheat produced in the U.S. are fed to livestock. The remainder of the corn and soybeans are either processed into biofuel or industrial food ingredients. And these are the crops the Farm Bill primarily subsidizes. Fruits, vegetables and nuts--the very items the USDA wants us to eat most of--are known as "specialty crops" and currently receive only a small fraction of farm subsidies despite their high nutritional values. Well over 60 percent of commodity subsidies flow to crops fed to animals.

It's the industrial beef, hog, chicken and dairy operations that win out; subsidies mean they get cheap feed. According to the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine, the meat, egg and dairy sectors were the beneficiaries of the majority of the $246 billion in subsidies given to U.S. food producers between 1996 and 2009.

2. Don't pay polluters.

Massive dairies, hog and poultry factories and other livestock feedlots house thousands (often tens or even hundreds of thousands) of animals. Some produce as much waste as the sewage system of a small city. The difference is that animal feeding operations don't install municipal waste treatment plants to clean up their messes.

And yet this type of food production has been supported for a decade by a Farm Bill program called the Environmental Quality Incentives Program. EQIP, as it's called, must spend 60 percent of its budget on livestock producers, many of whom are the worst, environmentally speaking. And what are they spending that money on? Manure lagoons and waste trafficking.

EQIP started as a conservation program, meant to help small livestock producers keep animal waste out of creeks and waterways. But now, thanks to lobbying, the massive animal farms can be reimbursed for up to 75 percent (capped at $300,000 per owner) of their costs for animal waste storage and hauling and compliance with laws like the Clean Water Act. Should we have to pay livestock operators to comply with basic laws? Should our tax dollars build the infrastructure for massive meat, egg, and dairy factories?

Meanwhile, EQIP funds to organic farming projects are capped at $20,000 a year per operator.

3. Don't subsidize overplanting.

Nothing in the Farm Bill--nothing--continues to be more counterproductive than the complete disconnect between commodity crop subsidies and conservation programs. On the one hand, subsidies encourage farmers to plant in every inch of soil, crop insurance programs eliminate farmers' economic risks, and disaster bailouts encourage plowing even on marginal lands in areas prone to flooding and drought. On the other hand, the U.S. Department of Agriculture directs less than 7 percent of its overall spending toward conservation, much of that to right past wrongs and to clean up problems stemming from over-farming.

Consider, for example, that even as 1.7 million acres were enrolled in the Conservation Reserve Program in South Dakota between 1985 and 1995, more than 700,000 acres of grassland were converted to crops--primarily corn and soybeans (already in excess supply). This absurd process only accelerated during the last Farm Bill, as even grasslands used for hay and pasture were transformed into corn fields. Such a dichotomy makes Farm Bill conservation programs seem more like a distraction than a coordinated national stewardship strategy.

In the case of the Wetlands Reserve Program--arguably the Farm Bill's most successful conservation effort to date--only wetlands previously impacted by agricultural development are eligible for funding; you can't use the money to save pristine ecosystems (unless they're attached to land damaged by farming or ranching).

4. Don't farm corn for fuel.

The drums are finally beating against ethanol subsidies and tax breaks that suck up $7 billion per year in tax dollars. It's about time. For years Congress has mandated that gas be blended with ethanol to push our fuel supply further. And yet, we're practically spinning our wheels backwards. It takes about two-thirds of a gallon of petroleum products to sow, fertilize, irrigate, harvest and process a gallon of corn ethanol. That's minimally cutting our dependence on foreign oil.

In fact, in 2010 a full 36 percent of the U.S. corn crop was turned into ethanol. That only displaced about 8 percent of what we put in our gas tanks. Americans could save that much gas with a 1.1 mpg increase in the fuel efficiency of our cars and trucks. Here's a kicker: Ethanol-laced gas actually lowers fuel efficiency by 3 to 4 percent.

America faces numerous and complex food- and farming-related challenges in the years to come: curbing the obesity epidemic, halting the loss of habitat, stopping disease outbreaks like e. coli, bringing up the next generation of farmers and ranchers, and many more. The Farm Bill is our chance to right things that are wrong with the food system. Even small amounts of well-directed funding can do a great deal for a beginning farmer education program, habitat restoration effort, or local food project. It would help if the Farm Bill could stop fighting itself. And maybe then it can start to align along one sensible strategy: Create economically and environmentally healthy farms to grow healthy and affordable food.

We Can’t Afford to Look Away

Copious column inches have been devoted recently to secrecy laws that are being proposed and voted upon in state legislatures to protect Confined Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs) from unflattering media attention. “Whistle blower” laws in Iowa, Minnesota, and Florida would make it a felony offense to gain employment for the purpose of producing videos documenting the realities of food animal production. The New York Times editorial board had this to say in late April:

“Exposing the workings of the livestock industry has been an undercover activity since Upton Sinclair’s day. Nearly every major improvement in the welfare of agricultural animals, as well as some notable improvements in food safety, has come about because someone exposed the conditions in which they live and die.”

Just this winter nutcases in Montana introduced a law that would allow representatives to carry concealed weapons in state capitol buildings. Do we find it surprising that states would also want to protect the sociopathic behavior behind closed doors of animal factories?

The CAFO industry and its evil twin, big agriculture, have been mucking with free speech, freedom of information, and basic democratic rights for over a decade. Oprah Winfrey was dragged through a prolonged and expensive lawsuit in the late 1990s for saying she had changed her mind about eating hamburgers after learning about industry feeding practices.

When sifting through 6,000 images for possible publication in CAFO: The Tragedy of Industrial Animal Factories, we learned that Montana, North Dakota, and Kansas had already passed laws making it illegal to photograph a food animal production operation without consent of the owner. Thirteen states had passed “veggie libel laws” making it a criminal offense to critique a food production operation. Needless to say, the 450 photographs and 30 essays that made the final cut were carefully vetted.

Many reactions to the images that finally appeared in CAFO follow similar lines: “it’s so heavy,” “I can’t get past the beginning,” of “I’d just rather not know.” A classroom of Bradford University political science students described the photographic content as “very intense.” Please consider this. Of the sixty-plus photographers that contributed images to the book, the largest by number came from photo agencies: the Associated Press, Corbis, Reuters, Alamy, and others. These photographers had permission to enter slaughterhouses, feedlots, and hog factories. Do you think they were shown the most down and dirty or the best of the best?

Facing the importation of the U.S. mega-dairy model into the United Kingdom, the World Society for the Protection of Animals (WSPA) sent a video team to America’s largest milk producing state, California, to see what they might be up against. The WSPA researchers were appalled at how easy it was to document blatant and abysmal animal welfare conditions. Should they be classified as “agro-terrorists” as the new anti-whistle blower laws proposed by industry suggests? Or should they be thanked for showing us a situation so desperately in need of improvement? After a prolonged campaign, the UK mega dairy withdrew its pollution permit—at least for the time being.

Meanwhile, in January of 2011, the Idaho legislature voted 61-7 to keep the public from knowing how dairy waste is handled. One wonders how legislators—charged with protecting the public good—can possibly pass a measure that prohibits its voters from being informed about something as potentially toxic as fecal floods of CAFO manure that can penetrate their drinking wells and groundwater.

These are Orwellian times. Many local governments have lost the ability to decide on whether or not to allow a CAFO in their communities. Those decisions are now made instead by state departments of agriculture, which are largely ruled by industry. Legislators turn their backs on freedom of speech and freedom of information to protect shit spewing polluters.

Citizens can’t afford to look away from the realities of basic economic production systems, whether we are talking about food, energy, shelter or anything else. What you don’t know can at least make you an accomplice in something you might not agree with, such as the abuse of other living creatures or ecosystems for the sake of a cheap meal. More than that, the democratic rights that we hold dear are ultimately at stake.

Is protecting the Fast Food Nation worth that price?

See also:

"Collaborative Approach Sets UK Apart on Animal Welfare"

A West Coast Healthy Food Uprising

The West Coast is a place where, on a rainy winter night, hundreds of people turn out to discuss food policy. People understand the connection between healthy food and community health. They see local and regional food as an engine to revitalize economies. Still I am often asked what audience members can do to affect change in the food system.

To my mind, individual action takes place in radiating circles, starting with the personal and moving out to the local, regional, state, national and global. I am increasingly drawn to the personal and local, where influence and outcomes are most powerful and tangible. Raise your own fruits, vegetables, or chickens and you know exactly what goes into the entire process. Work on a campaign to protect open space or build a school garden and you can have personal contact and investment.

Things are not so clear or accessible at the national level. The Farm Bill, driver of federal food policy, is so complex that it is hard to know where to begin. Absent campaign finance reform, you are swimming with the sharks: grain monopolies, corn growers, farm bureaus, livestock associations, sugar lobbies, ethanol processers that pour billions of dollars into the political process.

We can’t let this intimidate us from righting a broken food system. By pulling back to the regional level, it might be possible to form an alliance of concerned eaters with political power at the national level. In January 2011, the City of Seattle approved a Farm Bill platform. Given the growing awareness of the importance of food and farm policy on the West Coast, it is reasonable to expect that city councils in Olympia, Portland, Eugene, Ashland, Ukiah, Santa Rosa, San Francisco, Los Angeles and all the way down to San Diego may carefully consider and eventually sign on to a similar document. Its main tenets share a lot in common with a Farm Bill platform drafted by Roots of Change in Los Angeles in November 2010:

- a health centered food system;

- sustainable agriculture practices;

- community and regional prosperity and resilience;

- equitable access to healthy food;

- social justice and equity;

- systems approach to policy making.

While the Farm Bill is the Big Kahuna in the food and agriculture system, there are other forceful unifying levers. In 2008 California passed Proposition 2, an animal welfare initiative that will ban three forms of egregious confinement systems: cages for laying hens; confinement stalls for pregnant sows; and veal crates for male dairy calves. Proposition 2 can’t be dismissed as a purely California phenomenon. It passed with 63 percent of the vote. Seven states have now banned certain animal confinement systems, and the Humane Society of the United States has introduced similar initiatives in two more key states: Washington and Oregon.

In addition to unified Farm Bill platforms, imagine the entire West Coast agreeing on advanced animal welfare standards. Most citizens believe that food animals deserve humane treatment while they are alive, yet there are no laws at the national level to protect livestock during their production cycles. Intervention is still possible at the state level.

Health practitioners are also joining the food policy reform movement, concerned about the epidemic of obesity, diabetes, heart disease, and other nutritionally related ailments ravaging adults and children in their communities. They are following the lead of innovative programs like the California Farmers’ Market Consortium that links the food stamp program (SNAP) with regional growers of fruits and vegetables in 60 farmers markets, from Santa Rosa to San Diego. In key markets, SNAP recipients can receive up to double the value of their purchases of fruits and vegetables—money that goes right into the hands of farmers. They can also watch demonstrations on how to cook and eat more healthfully. Doctors are collecting data on the medical benefits of such programs to analyze their effectiveness.

Coastal livestock producers and consumers interested in high quality, pasture-raised animal food products are united around a common concern: a lack of slaughter facilities within reasonable driving distances from production centers. In years past, each large town had some sort of slaughter facility. But decades of massive consolidation have devastated local processing capabilities. Small-scale slaughter facilities are one of the crucial missing links in local food system capabilities. In California, for example, only a handful remain. Just as Farm Bill dollars once built the giant monoculture farming infrastructures and Concentrated Animal Feedlot Operation industry that dominate today’s food system, it can do the same for the modern pastured livestock movement. Assistance can come in the form of value added producer grants, loans, important research, regulations tailored to small-scale facilities—to complement necessary private investment. Reformers could ask for 10 new West Coast processing facilities, for example, in the upcoming Farm Bill as a pilot project.

In a relatively short amount of time Washington, Oregon, and California could become a regional force in the national dialog leading up to the next Farm Bill. If we citizens don’t impact policy at the national level, there are plenty of agribusinesses and food manufacturers already working to set the rules and spend taxpayer money for us. As the old adage says, we reap what we sow. The West Coast can set its own table.

What Industry Doesn't Want You to Know About Animal Factories

See no evil, hear no evil, eat no evil. This seems to be the operating principle behind a slew of recent legal initiatives aimed at sheltering animal factory agriculture operations from public view.

State legislatures in Iowa, Minnesota and Florida are now considering bills that would make it a criminal offense to gain employment for the purposes of videotaping what goes on the behind warehouse walls of Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations, or CAFOs. In March, theIowa House of Representatives passed such an anti- “whistle blower” measure, co-written by the Iowa Poultry Association, which is now before the State Senate.

Pre-emptive legal strikes by the CAFO industry to put a chilling effect on anyone considering tarnishing its public image are hardly surprising. Industrial animal food producers are reeling from a series of shocking undercover videos that expose the abuse and suffering on the disassembly lines of slaughterhouses and inside warehouses crammed with hogs, laying hens, and meat birds. Such imagery is hard to shake from your subconscious. (Just this week a video was released of a sick calf getting killed with a pickaxe.) Opinion polls consistently show that Americans are increasingly concerned about animal welfare and health standards, and often willing to pay more for them.

While the industry would like us to believe that what you don’t know can’t hurt you, we are barely six months removed from last summer’s recall of 500 million eggs due to salmonella contamination from just two CAFO operations in Iowa. In response, people flocked to farmers markets, specialty retailers, and other venues to purchase free-range, organic, and cage-free alternatives.

In fact, industrial animal agriculture has already made bold assaults against First Amendment rights. In three states—Kansas, Montana, and North Dakota—it is illegal to photograph a factory farm without permission of the owner. Thirteen states have passed agricultural disparagement laws—a.k.a. veggie libel laws—that restrict what can be said about perishable food products. None of these laws have been challenged in federal court. The Texas Cattlemen’s Association, however, engaged Oprah Winfrey in a prolonged legal battle in the late 1990s for claiming on television that she had been “stopped cold from eating another burger” after learning about cattle feeding procedures from reformed rancher Howard Lyman. The popular talk show host had both sufficient resources and determination to fight and ultimately won the decision.

Numerous states have passed Common Farming Exemptions, which essentially allow the industry to determine animal cruelty statutes by defining them as standard practices. Does this sound like the fox guarding the henhouse? While the welfare of our pets is legally protected, there are no federal laws that presently govern the raising of food animals. Food animals are protected during transport (very hard to enforce) and during slaughter (though this doesn’t include the 9 billion chickens raised in the United States each year.)

The real question citizens and our elected representatives should be asking is, what do the animal factories have to hide, and do we really want to be part of such a clandestine food system? Is a cheap bacon cheeseburger or bucket of chicken worth the loss of democratic freedoms? We are talking about food production, after all, not missile defense.

Dr. Temple Grandin, animal behavior specialist at Colorado State University and long-time consultant to the livestock industry, argues in her most recent book, Animals Make Us Human, for greater transparency. Animal food producing operations, she suggests, should be able to pass a random inspection test, where a non-expert can visit and intuit how well animals are being treated. The best facilities, in her opinion, have video cameras streaming at all times, allowing for constant monitoring. Dr. Grandin is far from a radical animal welfare activist, and remains one of the most respected people in the world on such matters.

Animal agriculture impacts the planet in powerful ways. Tens of billions of food animals consume vast amounts of feed, generate massive volumes of waste, and make cheap fat and cholesterol laden meat, eggs, and dairy products the centerpiece rather than a vital component of every meal.

Proponents have been arguing for years that industrial food production is necessary to feed the word’s ever-increasing population. Essentially we are being told that the CAFO industry is too big to fail. Research increasingly shows that modern sustainable agriculture operations can be equally or more productive than conventional ones: without federal subsidies, environmental impacts, and dubious health implications—or infringements upon constitutionally protected freedom of speech.

Organic and sustainable agriculture practitioners have spent the last thirty years with an open source approach to information about farming techniques. For the most part, what they have learned the hard way about chemical-free, soil enhancing agriculture is out in the open for anyone to learn. Certified organic and biodynamic producers are required to pay fees to third-parties to audit their practices.

Recent moves to pre-empt the public from learning about the sometimes unspeakable conditions of modern intensive livestock operations are just the tip of the iceberg. Local communities are being stripped of their powers to determine zoning and land use concerning agricultural operations. Why aren’t local citizens permitted the right to decide whether a CAFO can be sited in their community in states like Illinois and Iowa?

There is a lot more information that the consuming public might find useful about industrial animal food production: the quantity of antibiotics used during a given production cycle; the exact contents of feed rations; the quantities, content and dates of air and water emissions from a CAFO; the amount of federal subsidies that support a particular operation. All are concerns with real public consequences.

We all have to eat. But we also have a right to know. Food should not come at the expense of animal welfare, the health of someone else’s community, or perhaps most importantly, our democratic freedoms.

Tour de Stench

by Dan Imhoff

Packed cozily inside a pickup, six of us are heading down a two-lane country highway through a Western Kentucky landscape blanketed in snow. We’re on what our tour organizer, Aloma Dew, calls a “Tour de Stench,” exploring one of the United States’ increasing number of animal factory hotspots.

At one point, our driver, Gene Nettles, centers the truck in the road, tires evenly straddling the broken yellow line. “I’m in Tennessee and you’re in Kentucky,” he says to me, with a chuckle.

Industrial poultry houses have long occupied this lightly populated rural area, supplying the region’s two massive processing plants with a steady stream of factory farmed meat birds. This rise of poultry CAFOs here has been intentional — It’s not called Kentucky Fried Chicken for nothing. Among the rolling hills are vast fields of federally subsidized corn and soybeans. These are the primary feed ingredients for fattening broiler chickens, now crammed as many as 80,000 inside the newest windowless, temperature-controlled warehouses. The stubble from last fall’s corn and soybean harvests is still visible under the recent snowfall, pricking up in geometric patterns. On the bare branches of the few remaining woodlots that edge the fields, bird nests are everywhere. Hawks stare down from perches, scanning the ground for prey.

Spurred on by a nearby Tennessee hog corporation, Fulton County, western Kentucky is also becoming a magnet for industrial pork production. The Tennessee-based Tosh Farms corporation is what is known in industry terms as an “integrator.” They contract with Kentucky growers to raise hogs to their exact specifications. In essence, it’s more like a boarding arrangement. Growers construct houses at no small cost — $200,000 each I am told — then cram them full of animals that the integrator actually owns. The contractors are paid a fee for successfully raising pigs to slaughter weight. The downer animals — dead, dying, diseased, and disabled — and the vast amounts of waste the animals generate over their short lifetimes become the grower’s responsibility.

My companions tell me that integrator Jimmy Tosh was attracted to this area because of Kentucky’s comparatively lax enforcement of water quality regulations and favorable tax laws. Somehow, despite the massive amounts of waste emitted from such intensive concentrations of animals, new CAFOs are being issued zero discharge permits. The only possible explanation for how such daily volumes of urine and feces could possibly disappear without environmental or community impact is “magic.”

But to my co-travelers, these CAFOs and their associated problems are anything but magical. It is more typical that whenever and wherever a high concentration of CAFOs appears among rural populations, conflict and community strife also enter the picture — pitting neighbor against neighbor, at times family member against family member. This is also the case at hand. Scrunched in the front seat with me is Max Wilson, a conventional grain farmer whose 900-acre conventional corn and soybean farm is surrounded by three hog CAFOs, all within less than two miles of his home. His neatly cropped hair starting to gray, Wilson is tall and slender and looks more like a school board president than what one might regard as an environmental crusader. In fact Wilson is a local school board member. But he is also one of a dozen neighbors involved in a lawsuit against Tosh Farms. The impacts have accumulated over time —oppressive odors, declining property values, CAFOs sited closer and closer to residences. He and his neighbors felt they had no choice but to take legal action.

Soon we are face to face, and nostril to stench as it were, with one of the hog CAFOs at issue. Two long white windowless buildings, huge circular fans on their side walls, are sunk down in the snowy landscape. These are finishing barns, where young hogs are sent to eat until they reach slaughter weight — approximately 260 pounds. I am told that hog barn operators in these parts often file applications for pollution discharge permits by declaring just a few animals shy of the official EPA designation of a CAFO, which would be 2,500 for hogs over 55 pounds. (This strategy of cramming animals just under the minimum for EPA designation as a CAFO is being adopted in other areas as well.)

These barns also represent a return to an old style of hog CAFO known as a “deep pit,” referring to the 8 foot deep by 100 foot by 200 foot manure catchment directly beneath the building. It’s designed to hold a million gallons of urine and feces. Rather than first pumping it into an adjacent lagoon, the hogs live on top of their own waste. Gases such as ammonia, hydrogen sulfide, and other VOCs (volatile organic compounds) are vaporized or blown into the air with fans. The remaining waste is pumped out of the deep pit and plowed into the ground, sprayed onto fields, or distributed by the truckload in shiny stainless 6,000-gallon tankers — often at night. Other fans are used to suck the air out of the CAFO and replace it with outside air. Toxic fumes from beneath the barns could otherwise overwhelm the animals. (There are reports of animals dying just this way due to extended power outages.)

I am about 75 yards downwind from the nearest building and the odor is sour, ammoniated, and nauseating. It fills the truck cab in the few seconds it takes for me to open and close the door to take pictures. Max says he can smell it more than two miles away when the wind blows in the direction of his farm.

In addition to the two hog barns there’s a dead box, a concrete rectangle about the size of a 40-foot ocean shipping container. That’s where the mortalities go to be composted or picked apart by the scavengers. Dead boxes are standard on most of the hog CAFOs I have seen.

This area of rolling hills and wintry farm fields and remnant woodlots seems like it would be quite stunning in the spring time. One can imagine a thoroughly different kind of agriculture. Pastures could be restored to complement the feed grains, with livestock moving about these farms, rather than a complete separation of animals from the outside world and their farmers. Tree plantings could protect the soil and yield food on the hills and on highly erodible lands. One could envision more farmers too, a new generation of people participating in a more diversified agriculture and food system.

Given the recent economic realities of agriculture, where more and more power has been transferred to integrated processors and distributors, it is somewhat understandable that landowners have taken the gamble on these expensive operations. For many, owning a CAFO may mean the difference between survival and foreclosure. Often the payback on such investments can take a decade, however, and the return per animal can be marginal. Then there’s the issue of quality of life. If neighbors are complaining, one has to wonder what it’s like to actually live on one of these operations.

Faster than we know it, our tour de stench is over. I am left thinking, as I so often am, that it really matters whose side you are on in these seemingly intractable battles. I am on the side of the farmers and the animals and healthy farm communities, even if our food ultimately costs a bit more. No amount of cheap protein is worth tearing away the fabric of rural culture by stinking up the countryside and raising animals as if they were assembly line objects. Somehow we must find a way forward. We don’t need this kind of agriculture to feed the world as is so often claimed to justify the concentration of filth and misery these systems embody.

I believe the collective wisdom and desire for change is out there among us.